| The afternoon of Tisha B'Av has to be one of the oddest moments of the Jewish liturgical year. It just feels strange. This morning was the only morning of the entire year in which tradition says we do not wear a tallit for the morning service. For a person who davens (prays) regularly, the idea of saying the morning blessings and hearing the Torah read without a tallit on the shoulders just feels wrong. |

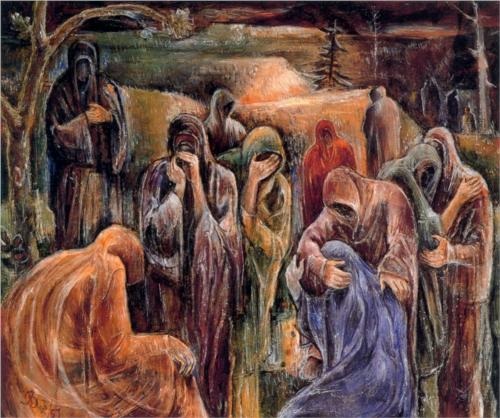

We have just spent the last twenty-or-so hours in the land of spiritual grief, reading the book of Lamentations both last night and this morning. Lamentations is the book that, at its cheeriest, asks God how much longer we must suffer. Perhaps we also have read kinnot, poems for mourning the destruction of the Temple. Then, on Tisha B'Av afternoon, the sound of the words changes completely. The haftarah is Isaiah 55:6 - 56:8, one of the most beautiful passages in all the prophetic writings. Isaiah inspires us with visions of a time of utter redemption:

The foreigners who attach themselves to Adonai to serve God and to love the name of Adonai to be God's servants—those who keep Shabbat from profanation and hold fast to My covenant—I will bring them to My holy mountain and I will rejoice in them in My house of prayer. Their burnt offerings and sacrifices shall be accepted upon My altar, for My house shall be called a house of prayer for all nations. (Isaiah 56:6-8)

It is one of the most hopeful and optimistic passages in the entire Hebrew Bible. It announces a time to come when all of humanity will be united in God. There will be no more distinctions between Jew and gentile. All will be one.

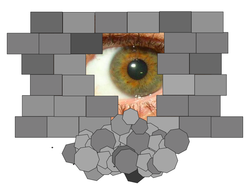

Why on earth do we read this at the end of Tisha B'Av, a day that peers into the abyss of human cruelty and despair? It is because it is only after we have taken that journey into the abyss that we can finally, truly, see the light of hope.

Hope is not just wishing for the best. Hope is what we experience after we have known despair and, yet, choose to see that it need not always be that way. You can only know hope after you have seen just how bad things can be. It is only after that experience that you can turn your life around and know that real joy is not just "having a good time." It is the feeling that your life has been reclaimed and restored by something beyond yourself.

That is where we want to get to before the strange journey of Tisha B'Av has been completed. We want to know that our highest hopes can be fulfilled, not despite life's torments, but because we have transcended that pain and risen higher because of it.

Other Posts on This Topic:

Not Turning Away from Grief

Tough Times

Devarim: How?

RSS Feed

RSS Feed