1) As rabbi, you attend community events because being part of a Jewish community is one of the greatest joys of your life—but also because it's your job. Members of the community sometimes feel uncertainty about this duality. Is s/he our rabbi because s/he loves us, or because we pay her/him? For congregants who are anxious about their relationships with parent-like figures, the tension can be painful as they seek reassurance that the emotional connection is genuine and not just professional. You just live with that.

2) Being a rabbi is a lot like being a community organizer. The main point of your job is not to do things yourself (except writing the odd sermon or teaching the confirmation class). Your most important job is to collaborate with others and give them the pleasure of succeeding for themselves. It means that you accept a lot of blame but don't take a lot of credit. You learn humility. You learn to derive satisfaction from helping other people to feel good about themselves.

3) As a rabbi, you are present at some of the most powerful moments of other people's lives. I remember visiting a mother in the hospital just an hour after her child was born. I saw her staring into the baby's eyes with such love, I felt like someone who had just stumbled into the presence of a couple's passion. I also remember being in a nursing home room when a man was saying goodbye to his wife of fifty years for the last time, weeping and declaring his love. The truth is—as difficult as it is to remember at such moments—people want the rabbi to be there. They want your presence to be a token of the fact that something powerfully meaningful is happening. Through your eyes, they want the universe to witness their pain, joy, spirit and existence. If you're good at what you do, you will resist the temptation to try to say something meaningful at that moment. Just be.

4) People assume that you have a lot of power in the congregation. They think that you get to decide all the important questions. The truth is, the only power you have is the authority you earn by being a decent human being and by helping people in the way that they actually want to be helped. Rabbis who say "No" a lot, and think that it demonstrates their power, are not usually successful.

5) Rabbis should be allowed to be spouses to their spouses and parents to their children in full view of the congregation. If you try to keep those roles separate from the role of rabbi, you lose the ability to teach your greatest lessons about living a life of Torah.

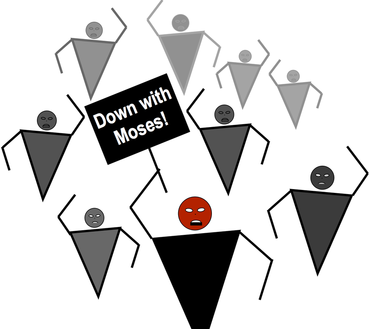

6) When you're the rabbi, it's your job to tell the people who pay you that they are being ganifs when they are being ganifs. Also, you have to do this with great love and compassion. If you don't, you should be fired. Is there any other job like that?

7) You go through five years of rabbinic school, in which you are trained to be knowledgeable about the intricacies of Hebrew grammar, the underlying structure of talmudic discourse, the historical context of the biblical text, and the nuances of the philosophies of Saadia Gaon, the Rambam, Buber and Heschel. Then you enter a congregation in which you teach adults their alef-bet and Bible stories. You breathe deeply. You smile. You appreciate the fact that it is all Torah and it is all holy. You love them deeply.

8) You never stop becoming a rabbi.

9) Your job is not to teach facts, beliefs or practices. Your job is to be the conduit through which other people fall in love with Torah. You must do this without them knowing it. You must make them believe that they are learning facts, beliefs and practices when, in fact, they are learning to become themselves.

10) It is not up to you to finish the job. However, neither are you free to desist from hearing people's stories, holding the hands of people in pain, shouting for joy at every wedding and bar mitzvah, striving toward God with every prayer (even when you're leading the service), feeling the loss experienced by every mourner, fighting like hell for justice, making every child feel great about being Jewish, learning more Torah, helping a community find its voice, hoping for the future, living with the past, accepting failure, saying you're sorry, returning to the place where you began, saying goodbye, and saying hello.

Goodbye, Congregation Beth Israel.

Hello, Temple Beit HaYam.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed