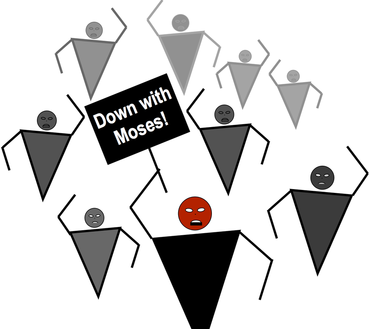

| When I know that someone is angry or upset with me, my instinct is to stay away. I don’t, go “looking for trouble,” as the saying goes. "If trouble wants me," I think, "let it come and find me." That's a natural human reaction. But staying away from trouble is often where real trouble starts. In this week's Torah portion, Datan and Abiram foment a rebellion with Korach against Moses. Why? Maybe they were afraid that Moses would lead them only to slow death in the desert. Maybe they felt marginalized by Moses' authority. Whatever their reasons—good or bad—it made sense to them to challenge Moses. |

Later, Moses called for Datan and Abiram to appear before him. They refused to go to Moses, and their words were as far from modest as can be imagined. They said, "We will not come! Is it not enough that you brought us from a land flowing with milk and honey to have us die in the wilderness, that you would also lord it over us?”

Moses, it seems, wouldn't go to them, either. Nobody likes to go looking for trouble.

Who is the good guy and who is the bad guy in this story? Most of the classical commentators are quick to paint a picture in black in white—Moses is the man of God and the rebels are selfish, narrow and power-hungry. But nothing in Torah is ever truly black and white. Moses may be a well intentioned leader and faithful to God, but that may not be enough.

Listen to what Rabbi Simchah Bunim of P’zhisha has to say. This hassidic master is one of the few commentators who is willing to find fault with Moses’ behavior. He asks, “Why did Moses have to send for Datan and Abiram and wait for them to attend to him?” Moses failed to bring peace to the Israelites during this, his greatest challenge, because he did not bother to go to them and try to appease them. Instead, he waited in his tent and sent to have them brought to him.

When I, like Moses, say, “If trouble wants me, let trouble come and get me itself,” in my mind I have reduced a human being to being nothing more than “trouble.” I have neglected to see the human aspect of the person whose needs and desires—no matter how base I may consider them—are nothing but a source of bother to me.

If I were to look at the human beings behind my “trouble”—I would begin to learn about who they are and what needs lie behind behaviors I, at first, labeled “selfish, narrow and power-hungry.” I would see people in pain, I would see people who feel excluded, people who want the same things I want—love, acceptance and an ear to hear their plight.

When our communities overcome the human tendency to see those who think or behave differently as “trouble,” we begin to create peace. When we take the time to see the human being on the other side of the divide, it becomes much harder for us to see the other person as a villain.

The Torah teaches that Moses was the most modest man on the face of the earth. Yet he, in all his modesty, was too busy burying his face in the earth—bemoaning his own sense of persecution—to walk to the source of his “trouble,” and begin to see, instead, a person.

May we, who have many points of view—we who are human beings who have each known pain, exclusion and isolation in our lives—come to truly see each other. Let us not wait for trouble to come to us, even when we believe ourselves to be in the right. Let us stand up, walk to trouble’s tent, and come to know the human face across from us.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed