| Today is Shushan Purim, a unique day in the cycle of Jewish holidays. Purim is the only holiday whose date depends on where you happen to celebrate it. For most of the world, Purim was yesterday. However, if you happen to reside in Jerusalem or the city of Shushan (where the story of Purim took place) Purim is today. Therefore, the observance is called "Shushan Purim." |

Queen Esther then instituted the holiday of Purim for the day after the Jews were permitted to defend themselves. It is an important distinction for the holiday. Purim does not celebrate a military triumph. It celebrates the day of "rejoicing and feasting" that followed. That is why Purim is on the fourteenth day of Adar, not the thirteenth.

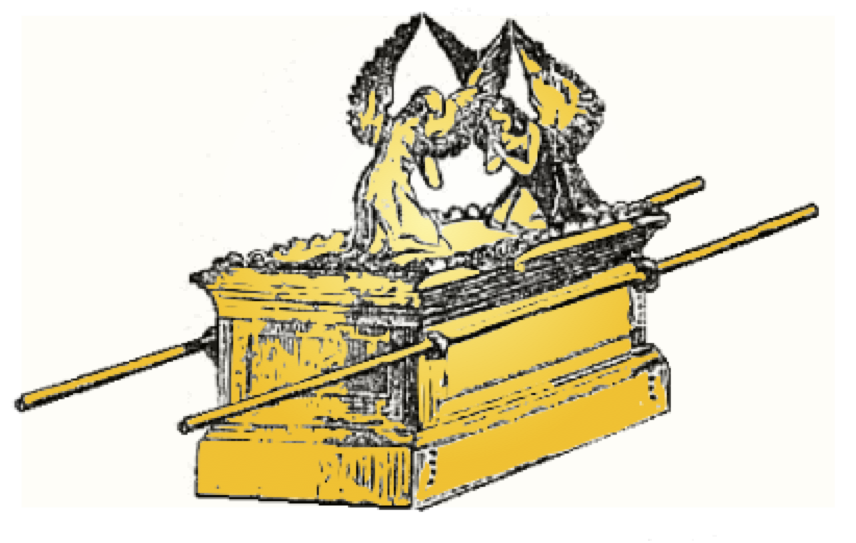

However, the text tells us that in the capital city of Shushan, the King permitted the Jews to defend themselves for an additional day. They fought against their enemies on both the thirteenth and fourteenth of Adar. The book of Esther is careful to explain, therefore, that Purim could not be celebrated in Shushan until the fifteenth day. On that day, the Jews of the capital would follow the Jews of the "unwalled towns" of the kingdom by "sending gifts to each other" (Esther 9:12-19).

This is the reason that Purim still is celebrated a day late in Shushan and in Jerusalem, whose walls were standing back in the days of Joshua. Today is the day that Jews in Jerusalem read the Megillah with its blessings and deliver mishloach manot, gifts of food, to their friends.

For people today who are concerned with reviving and reinvigorating the joy of Judaism, Shushan Purim has an important lesson. We must be careful to be clear about why we are celebrating. We change the date of a holiday to avoid even the appearance that we are celebrating the downfall of our foes.

Real joy is not about triumphalism. We do not rejoice over the death of Haman. We do not celebrate by firing our weapons into the air. Rather, our best celebrations are always about gratitude. We wait a day after our temporal victory and rejoice, instead, over the miracle of an unseen presence who delivers us and guides us. We celebrate by laying down our weapons and taking a bag of cookies over to our neighbors' homes.

That is something to be joyful about.

Other Posts on This Topic:

Imagine There's No Haman

Purim: Who Knows?

RSS Feed

RSS Feed