I want to introduce you to Rosie. It’s not her real name, but she is a real person, a Jewish woman who lives in Rhode Island. Like millions of other people of all religions, races and ethnicities across the United States, Rosie lost her job within the first month of the COVID-19 pandemic and needed help. Without her income, she was in danger of not being able to pay her utility bills, buying food, or even keeping her home. Fortunately for Rosie, she had some previous familiarity with Jewish Collaborative Services of Rhode Island and she sought their assistance.

Rosie spoke with Marcie, the coordinator of the Full Plate Kosher Food Pantry, and she received an emergency delivery of food, along with other household supplies and personal care products. (By the way, the Full Plate Food Pantry is the agency that we are supporting this year with our High Holy Day Virtual Food Drive.)

Rosie also connected with a case manager at JCS who was able to give her money from a designated COVID-19 relief fund to help her pay her utility bills and rent.

Rosie was so thankful for the help that she sent a note to the agency. She wrote, “Though I am certainly grateful to JCS for the financial support, food and supplies, I am most grateful for their caring and compassion. I turned to Shana from the Kesher program when I felt the worst. When I was fearful about my future, Shana listened and cared.”

Now, you might think that I am telling you Rosie’s story today to give the Jewish community a pat on the back for taking care of our own. Yes, Jewish Collaborative Services does an amazing job. Yes, I encourage you to support their work with generous donations. Yes, we at Temple Sinai are so lucky to have Shana Prohofsky, the woman Rosie praised in her letter, as our Temple’s Kesher Worker and I encourage you to seek her help whenever you are in need.

What may not be clear, though, is that this is not really such a happy story. Even though Rosie got help, there are many others who do not. Even for Rosie, this was a painful experience. It’s always hard to admit that you need help and to accept food and money. There is an aspect of the experience, even when it is most deeply needed – even when the people offering help are loving, kind and supportive – that causes people to feel humiliation and despair. Nobody likes feeling that way – nobody – and we should not be content with a society that forces anyone into that position.

The reason why I am telling you about Rosie today is because there are millions of Rosies out there – in Rhode Island and beyond – people who are struggling with poverty. And, the difficult truth is, if you have never experienced poverty, it’s difficult to imagine how hard it is – how poverty traps people over generations – how not having a job means you can’t get a job – how lenders, financial institutions and the legal system prey on poor people – how having to struggle to feed your children makes everything else in your life a thousand times more difficult – how falling into poverty eviscerates people’s self-esteem and how they are perceived by others.

Poverty is an issue that many of us are entirely blind to. But it is a problem – a huge problem – right here in our state and in our community. Rhode Island has the highest poverty rate in New England at 13.4%. One out of every seven and a half residents of Rhode Island lives in poverty – more than 136,000 people. And although poverty is a real and significant problem in the Jewish community, as you probably know, it is far worse in other segments of the population.

We may think that we are a state that doesn’t discriminate on the basis of race, gender and age, but poverty in Rhode Island definitely does discriminate. The poverty rate for Black people in Rhode Island is 24% – one in every four Black people in our state lives in poverty. For Hispanic people, the rate is nearly 29%. For women of all races in Rhode Island, the poverty rate is 2.5% higher than it is for men.

What age group do you imagine suffers the worst poverty in Rhode Island? If you guessed the elderly, you are looking at the wrong end of the spectrum. It’s children. The poverty rate for people under six years old in Rhode Island is 22%. Almost one in four infants, toddlers and preschoolers in Rhode Island is living in poverty. Right now.

Homelessness is at a particular crisis point in Rhode Island. Every year about 4,000 men, women and children experience homelessness in Rhode Island, largely because our state lacks enough affordable housing units, and that results in sky high rents. The situation is so bad that – listen carefully – there is not a single town in the state – not East Providence, not Woonsocket, not Central Falls – where the average family seeking to rent can afford the average priced two-bedroom apartment. Think about that.

No matter what image comes up in your mind when you hear the term homeless, it is almost certainly wrong because there is no one type of homeless person. Homeless people are single people and they are families with children. They are people who are out of work and they are people who have jobs. They are people living outdoors and in shelters, and they are people who move from one friend’s house to another or live in their cars. They are middle-age, elderly and, increasingly, they are children. Over the past six months, I have had no fewer than three people from this Jewish community approach me for help because they are homeless or are in imminent danger of becoming homeless.

I should not have to tell you that this is not the way a just society is supposed to be. This does not meet the standard of what Jewish tradition demands. In today’s haftarah, you heard the words of the prophet Isaiah who said that a fast on Yom Kippur that is only about begging God for forgiveness while, at the same time, allowing people to go hungry and homeless is no fast at all. Such a fast will not, in Isaiah’s words, “lift up your voice before heaven" (Isaiah 58:4).

So, what can we do? There actually is a lot.

Over the past several years, Temple Sinai has joined with the Rhode Island Interfaith Coalition to Reduce Poverty in support of legislation to combat homelessness, hunger and poverty. Many of you will remember the speakers we have had at our Friday night services talking about these issues and many of you have participated in writing letters, calling lawmakers, and testifying at the State House.

That work has paid off. This spring, our efforts resulted in a state law that now makes it illegal for landlords to discriminate against people who use federal housing vouchers to pay their rent. Such discrimination used to be so widespread in Rhode Island that classified ads said explicitly “No Section 8” – no federal housing vouchers. That will not happen any more.

This year, we also passed the Fair Pay Act to protect women and people of color from being paid less than men and white people doing the same work with the same qualifications. We passed the first increase in 30 years of RI Works benefits, which go to the poorest of the poor families in the state. We passed the Rhode Island Minimum Wage Bill that will increase the hourly wage of $11.50 to $15 an hour over the next four years.

These victories are enormous for struggling families and individuals in our state like Rosie. The 30% increase in the RI Works benefit alone will help thousands of children growing up in families without certainty about their next meal, adequate clothing, or even a roof over their heads.

But, of course, these victories are not enough. In order to answer Isaiah’s charge, we still need to make sure that Rhode Island is a state where our society’s wealth is not concentrated into the hands of a few wealthy people at the top with a multitude of poor people at the bottom. We need to make our state into a place where we recognize that our first obligation is to see that everyone’s basic needs are met with dignity, care and justice.

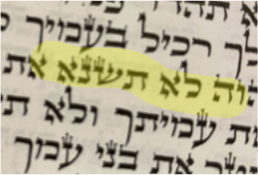

Over these High Holy Days, you have heard me talk about making this the year of “You shall not hate.” You’ve heard me say we have an obligation to care for each other by getting vaccinated to stop COVID -19. You have heard me talk about releasing ourselves from bitterness and toxic refusal to forgive. This morning, I need to ask you to go a step even further. I need to ask you to do something to end the pain and humiliation of poverty.

There are many ways of doing it and of making a difference. You can see it in the variety of ways that Temple Sinai members are changing lives. Susan Sklar, the Chair of our Social Action Committee and other Committee members made a difference this year by organizing a phone calling campaign to get Temple members to call lawmakers about legislation – now passed – that sets standards for care in our state’s nursing homes.

Our members Marc and Claire Perlman made a difference this year by raising millions in cash and products for the Ocean State Job Lot Charitable Foundation to feed the hungry, shelter the homeless, assist military families in financial crisis, and help people in need due to COVID-19.

Our members Shelley Sigal, Tonya Latzman and many others made a difference this year by participating in the Temple’s “I Can Run Errands for You” program, doing grocery and pharmacy shopping for seniors in our community who are not able to get out of their homes during the pandemic.

So, what about this new year? And what about you? What difference will you make in Rhode Island and in the world? It does not need to be big and it does not need to take a lot of your time. Just believe me when I tell you that for someone like Rosie, or the more than one hundred thousand other people in Rhode Island living in poverty, it will be enormous.

G’mar chatimah tovah.

May you be sealed for a good year.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed