How could there be a more terrifying moment for a rabbi than to stand where I am standing right now. It’s Rosh Hashanah. I am the new rabbi, here before the entire congregation for the first time, and you are all expecting and hoping that I will say something brilliant. I am doomed.

So, instead, let me say something appropriate to this holy day: I'm sorry. Forgive me.

I am new here, I don’t know all the history and all the customs of Temple Sinai. I will make mistakes. Forgive me when I forget your name at the most embarrassing possible moment. When I stumble through your favorite Hebrew prayer, please, forgive me. I am sorry.

Five years of rabbinic school and fourteen years as a congregational rabbi is a significant amount of time. Over those years, I have learned a lot about how Jewish communities work and how to teach our tradition in ways that touch people’s minds and hearts. I have celebrated with families on their joyful occasions, and held their hands in moments of grief. Yet, despite all those experiences, my rabbinic education is still incomplete. I still have a lot to learn. I look to you, the congregation I now serve, to be my teachers.

So, when you come to me with a crisis in your life and I bumble for the right words to express my concern and sympathy, please know that I am sorry. When the day arrives that you come to services expecting your spirit to soar, and instead, you end up hearing me sing off-key, please know that I am sorry. I have a lot to learn.

I know that I am not the first rabbi you have had, either here at Temple Sinai or at other congregations where you have been members. I know that my predecessors were not perfect, either, but, still, you should know that my mistakes will be different from the ones they made. I will amaze you with my originality.

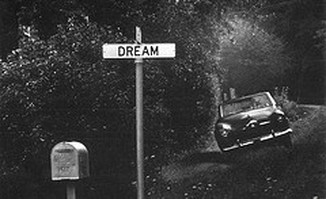

I know that you have high expectations for me based on your lofty dreams. That’s good. Dreams keep us moving forward, changing and renewing. In the last few months I’ve learned about some of your dreams – the dream of a new start for a congregation that is filled with optimism for its future – the dream of building on past successes with new growth and dynamism – the dream of expanding opportunities for adults to learn about Jewish thought, tradition and practice – the dream of building the congregation’s membership and strengthening its financial health.

Most everyone who studies to become a rabbi does so with some idea that there is – somewhere out there – a community that he or she can make better and that will bring out the best in him or her. Just as you brought me to your community with the hope that I could help you find new directions and realize your dreams, I also came with hopes and dreams of my own.

I come hoping to fulfill a vision of a congregation in which Judaism comes to life, a place where people find new meaning in their lives and a sense of spiritual fulfillment. I hope to help create a place where children and their parents can love learning together, a place where people have new insights about themselves and their relationship with God, a place where “community” is a word that means a group of people who genuinely care about each other, help each other through troubles, celebrate joys together, and find it within themselves to forgive each other’s flaws.

Cantor Wendy, who comes to Temple Sinai with me in this new adventure, also has dreams she brings with her to this congregation, the first she has served as the lead cantor. In the three months we have worked together, I have seen that her dreams, too, are joyful and full of life and hope. I see her passion to serve a community that truly loves to express itself in song.

So, we all have come together to share each other’s dreams. We all have big, bold dreams – probably bigger than we can expect to be realized fully. But that is the nature of dreams. We are in a relationship now – congregation, cantor and rabbi – and relationships are built on mutual commitment, mutual forgiveness, and, most of all, on sharing dreams. The best relationships happen when people are willing to listen to each others dreams and to answer with their own.

Cantor Wendy and I have been amazed by how much you have turned toward us and shared yourselves with us in welcome and in friendship. We hope that we can reciprocate in turning toward you – but remember, you have a big advantage over us – there’s only two of us.

Relationship building is also a way of describing what the High Holy Days are about. We are called to make t’shuvah, which we usually translate as, “atonement” or “repentance,” but which literally means “answering,” or “turning.” At the most basic level, the Days of Awe are the time when we are called to turn toward God – to answer and continue the conversation, to renew our relationship with That Which Is Beyond Us.

This is a way of talking about God which many Jews find difficult. Entering into “a personal relationship with God” does not sound very Jewish to many of us. It reminds us of the catch-phrases of Christian fundamentalists. But relationship can be a deeply Jewish way of thinking about God.

To Martin Buber, the great 20th century Jewish philosopher, relationship was the key to understand God as a reality. Buber wrote that God is found in relationships where two human beings accept each other in their entirety without preconception or expectation. Seen in this way, t’shuvah, returning to God, is the process of re-examining the relationships in our lives and striving to accept others just as they are. Our relationships are a reflection of how we relate to God. Repairing our relationship with God means repairing our relationships with other human beings, especially the people who are closest to us.

We ask ourselves at this time of year about those relationships: Have we treated people in a way that respects their unique dreams and aspirations, or have we made them adjunct to our own desires? Have we allowed ourselves to know in their entirety the people who are close to us – their many potentialities along with their faults and shortcomings – or have we befriended only those aspects that are most appealing or useful to us? Are we open to who they are now – constantly changing and growing – or are we stuck in perceiving them as they once were? Are we willing to say, “I am sorry. Forgive me,” when that is called for?

When we truly do make the effort to see others as total human beings – when we seek to know them, understand them, listen to their dreams – we come a little bit closer to reaching our own humanity.

This is a paradox. Our dreams are what make us real, both to others and to ourselves.

If I do not see your dreams, you will not be real to me. If you do not see my dreams, I will be just an object in a set of robes, playing the role of a rabbi. Since we are in a relationship with each other, we are in conversation. We tell each other our dreams, each answering with our own dreams. Rabbis come to congregations as a place to make a living, to try out their ideas, and to be leaders. Congregations seek out rabbis for their programs and services, for opportunities to learn and to be led. When the relationship really works, though, each finds something more. In coming to know each other, rabbis and congregations help to make each other more real – like the velveteen rabbit in the children’s story. We give each other meaning by accepting each other as we are – our dreams along with our flaws, our triumphs along with our mistakes.

Not fourteen, not twenty, not one hundred years of rabbinic experience could teach me to know who you are. Despite the certificate hanging on the wall in my office that calls me, “Rabbi,” I cannot truly be your rabbi until I have learned from you, who you are and who you yearn to be. It is, of course, a process that can never end, since we are always becoming something new – and we can never be entirely sure just what it is we are becoming.

But that’s okay. Relationship means acceptance and forgiveness. Please forgive me my shortcomings and failings. I will forgive you of yours. In this way, together, we will continue the conversation and continue to share our dreams. On this Rosh Hashanah, when we seek to turn to God, we can begin by turning toward one another in acceptance. That is how the journey begins.

L’shanah tovah tikateivu.

May you be written for a good year.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed