A synagogue does not exist to raise money. It exists to be a community.

A synagogue does not exist to raise money. It exists to be a community. Unlike the houses of worship of other faiths, Jewish temples and synagogues in North America require their members to ante up large annual dues payments. For many congregations, dues are in the lofty neighborhood of $1,800 a year or more. Some large urban congregations have annual dues that are two or three times that amount.

Almost all congregations have a process to reduce dues for members who cannot reasonably afford the standard rate. Often, members seeking a reduction must meet with or write to congregational leaders to explain their need. Some congregations require them to provide documentation of their financial situation. For those who find that process humiliating, insulting or aggravating, the only alternatives are to pay full-freight or to not affiliate.

Anyone who has held a leadership position in a Jewish congregation should understand the ideas behind this system. The Temple needs money to exist and everyone has to pay his or her share. Without requiring members to give at a level that will allow the congregation to meet its budget, how could the congregation survive?

For a long time, this system worked. Many Jews thought of Temple dues as "the Jew tax" — the price that they were required to pay to make sure that there would be a place for them to worship, to give their children a Jewish education, and to bury their dead. It was part of the Jewish social contract. A few people always grumbled about it, but as long as their numbers were few, it did not matter.

There is increasing evidence, though, that this system is breaking down in the early 21st century. Many Generation X Jews no longer feel obliged to pay large amounts annually to be part of the Jewish community. For some, Judaism just isn't a high priority compared to other demands for their dollars. Others would prefer to pay for their Judaism à la carte, hiring a rabbi when they need a wedding, bar mitzvah or funeral. There are also Jews who say that synagogues and temples have become hypocritical, caring more about their members' money than about living a Jewish life. And it is not just the Gen Xers. I have heard plenty of Jewish grandmothers and grandfathers tell me that Temple dues are insulting.

Here is the truth as I see it: In some congregations, the present system of dues has become destructive to our mission. We are supposed to be promoting values of compassion, generosity and inclusion. But, sometimes, we are making people feel coerced into paying what they don't think they should have to pay. Our leaders often feel resentful toward Jews who don't "pay their share." We risk creating the impression that our congregations are country clubs. A religious organization cannot sustain itself if it harbors and promotes such coercion, resentment and negative impressions. If the institution of the synagogue is going to survive the 21st century, it has to adapt.

Articles questioning the dues system in North American synagogues have appeared in eJewish Philanthropy, Reform Judaism Magazine, The Forward, The Washington Post, Newsweek, and The New York Times. Asking out loud if we should get rid of dues is no longer a cutting-edge or anti-establishment posture. It is the opening to a necessary conversation about the future of the Jewish community.

There is now a small movement of congregations that are asking just these questions. This spring, the congregation I serve joined them. We are scrapping dues.

Temple Beit HaYam in Stuart, Florida, recently sent a letter to its members announcing that it is changing from a dues system to a pledge system. Instead of telling members how much they have to pay, the congregation asks members to pledge the amount they wish to give as their annual financial commitment. Each year, the congregation will calculate the average level of giving needed to support its programs and services based on its budget, membership, and other sources of income. Members will be urged to try hard to reach or exceed the "sustaining amount," but each member family will decide for itself how much to give.

Also under the new system, families headed by adults under age thirty-five are asked to pay no more than $500 a year, no questions asked. Those are the folks who are going to build the congregation's future. We need them a lot more than we need their money.

Of course, adopting this system is risky. Everyone involved in the decision to do away with dues worried that, given the choice, many members would pay less. The results so far, though, have validated our hopes, not our fears. A large majority of those who have responded to the letter have committed to give to the Temple at the sustaining level or to exceed it. Phew. We really do have a generous congregation where people care about community. I think that most congregations are like that.

I am not advocating this exact system for every congregation. It is entirely possible that our congregation will need to adjust the new system in the coming years. It is still early in what I believe will be a new chapter of the history of the North American Jewish community. Congregations are different and every community will need to do what works best for itself. Yet, I applaud our congregation's lay leaders for trying something new to respond to a real change in our society.

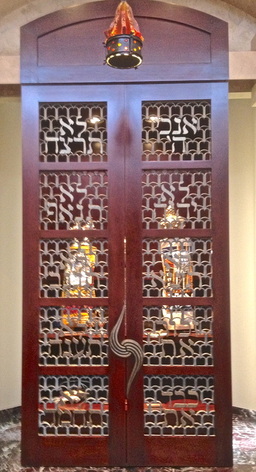

The purpose of a Jewish congregation is not to raise money. It is to celebrate our tradition, to find joy in being a community of compassion and giving, and to express our yearning for God. When the workings of our institutions get in the way of those goals, we need to find a way to do things better. When we unintentionally turn so many Jews away from our congregations, we need to open the doors and let them in.

Other Posts on This Topic:

Joy and Obligation

Re'eh: Giving and Receiving

RSS Feed

RSS Feed