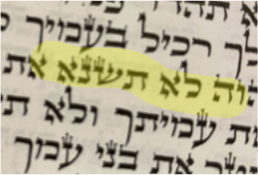

Hamas' surprise attack against Israel began in the early hours of Saturday morning. Not only was this Shabbat, in Israel it was also the holy day of Simchat Torah – the day on which we renew the annual cycle of reading the Torah, the day on which we read the last verses of Deuteronomy and then immediately read the first verses of Genesis.

Also, this week, for Jews around the world, we are in the week of Parashat B'reishit, the Torah's first weekly portion that brings us back to the story of creation.

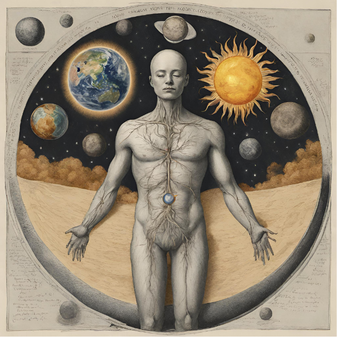

A close reading of the opening verses of Parashat B'reishit shows that God's act of creation was not a creation ex nihilo, creation out of nothing. The text says that when God began to create, v'haaretz haytah tohu vavohu, "The earth was chaos and unformed" (Gen. 1:2). God's act of creation was not simply a summoning of the world into existence out of nothingness. Creation is depicted as the process of imposing order, meaning, and moral value out of the chaos.

God does not just create light; God separates light from darkness and gives them the names of day and night. God calls it good. God does not just wave a magic wand to make earth, sea and skies appear; God divides them from each other, creates their categories, gives them names, and calls it good. God does not just decree the existence of plants and animals; God places within them the capacity to reproduce in a cycle of life, and God calls it good. To create the world, God gives the world structure, meaning, pattern, and purpose.

This gives deeper meaning to the statement in this week's Torah portion that, after creating human beings on the sixth day, God commanded them to have dominion over the world and all the living things in it (Gen. 1:28), and also that human beings should till and tend the earth (Gen. 2:15). These verses tell us that God made us to help fulfill the divine intention of a world sustained by a vision of order and striving toward what is good.

This is our job. This is what we are here for. The most basic purpose of human beings in this world is to be God's partners in turning chaos into order and meaninglessness into meaning.

On Saturday, we saw, unleashed from the Gaza Strip, the advance of the forces of chaos. There is no other way of looking at it. The savage attack against the people of Israel, that has already resulted in the loss of more than twelve hundred lives in Israel and in Gaza, was an act of utter moral depravity and a dive into the abyss of meaninglessness.

There is no argument to the contrary. Tragically, Hamas' attack cannot and will not result in anything like peace, stability, or national self-determination for the Palestinian people. There can be no good that will come of it except for those whose power is enhanced by rising levels of anger and lawlessness.

This is why, in a very deep sense, our response to this horrific war cannot simply be to beat back the enemy with superior power and to exact punishment against aggressors. If it were, we would reduce this conflict to the moral significance of a sporting match in which the score is kept by counting the body bags. The task before us is much deeper than that. It has to be.

In the face of those who would reduce our world to the empty and meaningless pursuit of power for the sake of power – through murder, destruction and escalating levels of anger – we must be the ones who say that we have not forgotten the purpose for which God created us. We will be the ones who assert meaning instead of meaninglessness, order instead of chaos, morality instead of lawlessness, compassion instead of cruelty, peace and love instead of mindless violence.

The journey toward that goal is difficult. Calls for peace and compassion, kindness and love – I know, I know – are not easy to swallow when we are confronted by the murderous cruelty we have seen in the past few days. And we are, indeed, obliged to wish success on the battlefield to those who are fighting to defend Israel. We are obliged to support them in any way we can. Yet, we also have an obligation to be mindful of the mission to bring order and meaning even to a situation where chaos reigns. Maybe even especially in a situation that seems to be lost to chaos.

How do we do that? By acknowledging our pain and not pushing it away. By being sources of comfort to those in distress. By holding the hands of those who are bereaved. By hearing the cries of those awaiting news about loved ones who have been taken captive. By burying our dead in the act that we call chesed shel emet, true lovingkindness. By recognizing the horrific pain of mothers and fathers who are watching their children go off to fight yet another war to protect our beleaguered people. By identifying with the unknowable sorrow of those who must send others off to fight.

And, we do it by remembering and sympathizing with the hundreds of thousands of innocent people in Gaza who are also the victims of Hamas' cruel despotism in this present situation. Even if we imagine them to be people who do not yet know their right hand from their left, we are commanded to care about them. That is our job, too.

We cannot lose sight of this duty. We cannot forget in the midst of our anger and our desire to annihilate the enemy – literally, to make them into nothing – that we are here in this world for more than the emptiness of power without compassion and anger without principle. We cannot forget that we are God's partners. We cannot forget to cry tears that do not just taste of bitterness, but also of heartfelt sorrow and of hope. We cannot forget to be human. This is why we are here. This is what we were made for.

The world was created by turning chaos and emptiness into order and meaning. And ever since that moment, the forces attempting to turn the world back into its primordial state of tohu vavohu have been hard at work. We will not let them win. We will stand for our people. We will stand for humanity and for all that makes us human.

Am Yisrael Chai.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed