What do you do, when it’s just you, and there is no God in sight to tell you what to do?

What will you do when it’s all up to you to figure out how to get through life’s pain and hard choices, too?

What will you do to find out what is true when there is no God to make it easy for you?

The book of Genesis opens with God loud, powerful and very present. God announces, “Let there be light!” and light comes pouring into reality out of the nothingness (Genesis 1:3). It’s God’s world. It’s all about God.

But God needs there to be more than just God. So, as Genesis progresses, God creates human beings. Then God gets frustrated with the human beings, their disobedience, their arrogance, their violence. God decides that it’s time to drown the human beings because they can’t learn how to behave (Genesis 6:6-7). And just when it looks like the story is going to end before it even gets started, God sees Noah (Genesis 6:8). God sees that despite all the darkness of humanity, Noah tries to increase the light, to do what’s right, to be a mensch. For his sake, for Noah’s sake, God decides to keep the experiment with humanity going, just to see what these human beings might be capable of.

God makes a covenant and decides that Abraham will be a messenger to show other human beings how to do things right (Genesis 12:2). Abraham’s great. He’s faithful and loyal. He passes every test, until, one day, God asks him to kill his son, just to see how loyal he really is. And Abraham, well, he almost goes through with it (Genesis 22:10).

That may have been God’s first moment of saying, “Now wait a minute. Was that the right thing for Abraham to do? Was that the right thing for Me to ask him to do? How much longer do I want to keep treating these human beings like puppets on a string, an experiment in my laboratory, swooping in with punishments, rewards, tests and judging everything they do? Maybe, they need to learn to get along without Me. Maybe, I need to learn to back off, and not be such a helicopter God.”

And that’s when God begins to fade from Genesis. Oh, sure. God talks to Issac (Genesis 26:2-5) and has a wrestling match with Jacob (Genesis 32:29). God shows a ladder between heaven and earth (Genesis 28:12) to remind us that there is still divinity in the world, even if it’s really hard to see most of the time. But no more tests. There are no more one-on-one chats with God in the book of Genesis. No more warnings about what challenges are around the corner. God decides to start letting us figure things out for ourselves.

And then there is Joseph. God spoke to Joseph, but only in dreams. And these dreams were almost like they were written in code. Joseph had to decipher them, find a key to unlock them. Joseph only got to see God in the darkness of slumber-time shadows, never by the light of day.

Poor Joseph. He never saw what was coming. Here he was thinking that God was going to be his personal guardian, like God was for Abraham, Isaac, and his father, Jacob. Joseph thought God would show him everything in those dreams to pave his way to success and glory. He could not have been more wrong.

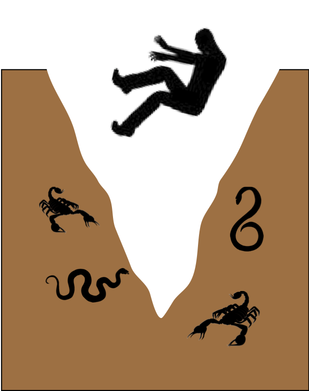

Joseph did not even notice how much his ten older brothers hated him (Genesis 37:4) when, BANG, they threw him into a pit (Genesis 37:24). He was still hoping that they would have pity on him when, BANG, they sold him into slavery (Genesis 37:28). He thought, surely, God would send someone to save him, when BANG, he was thrown into prison on a false charge (Genesis 39:20). He was alone in the darkness with no family and no friends, just a very quiet God (Genesis 39:21).

Joseph had a lot of growing up to do in that prison cell. In the damp dark, he must have felt really alone, isolated, friendless. He must have thought a lot about God’s new plan for human beings. He must have thought a lot about how, if he was going to have a future, he would have to create it for himself. He must have become determined that he would do it all himself.

And then, one day, opportunity came. Pharaoh’s baker and wine steward were thrown into the prison cell with Joseph (Genesis 40:3). What’s more, they had dreams – Joseph’s specialty. He listened to them, told them what their dreams meant, and figured it was just a matter of time before his extraordinary talents would get him out of jail (Genesis 40:14). And so it was.

The next time Pharaoh needed someone to solve a dream, there was Joseph. Joseph told Pharaoh what he needed to hear, gave him a plan to conquer seven years of drought, and Joseph got himself a job as Pharaoh’s number one grain storage and distribution agent. Joseph had done it all himself, without his murderous brothers, without his family, and without God saying even a single word (Genesis 41:38-40).

And then, one day, Joseph’s past showed up at his front door, the painful past that he thought he had put behind him. Ten brothers he could never forget. What’s more, they were desperate for food, and he was the one person who could give it to them. Ten brothers who had once thrown him into the pit, sold him into slavery, left him for dead. Ten brothers who had no idea that their fate was now in the hands of the one man who had reason to hate them beyond hate (Genesis 42:3).

What was Joseph going to do? God wasn’t there to tell him. All he had was a memory of pain, anger, frustration. And so, Joseph decided to bide his time. The brothers would not recognize him through the mask of his new Egyptian identity, so why not indulge in a little bit of – emotional torture?

He asked them about their family. They told him a sorrowful tale about their two youngest brothers. One, they said, had died long ago. (And Joseph must have said to himself, “That’s me and they don’t even know it.”) And, they said, the very youngest of them all, still a boy, was the darling of their dead brother and the apple of their father’s eye (Genesis 42:13)

“Bring this youngest one to me,” Joseph demanded. “We can’t,” the brothers said. “Our father would never allow it! Not after already losing one son.” But Joseph just cut them off and said, “Bring him or starve. Your choice. You decide” (Genesis 42:15).

Joseph was not done with torturing his brothers. He knew they would have to come back with Benjamin, his little brother, and then he would get his payback. He would hurt those men who had stolen his childhood, stolen his father, stolen his light and left him in the darkness.

His plan was to frame them. He planted a silver goblet in Benjamin’s grain bag (Genesis 44:2), had him arrested, and told the others that he would make Benjamin his slave (Genesis 44:17), just as the ten older brothers had made Joseph a slave so many years before. Revenge is sweet.

Until it isn’t. Which is what happened when one of the brothers -- Judah, the one who had the idea long ago to sell Joseph into slavery (Genesis 37:27) -- began to speak. Joseph heard him, still wearing the mask of his deception, and his brother’s words cut into his soul.

“Please,” the brother said. “Don’t do this,” the brother explained, “Not for our sake, but for the sake of our father. He is so old. He has grieved every day for the loss of his son, the one who disappeared all those years ago. If he loses this youngest one, too, he’ll just die from the pain (Genesis 44:22). Please,” he said, “Please, take me instead, for how can I bear to see my father tortured? Take me instead so I don’t have to see it all happen again” (Genesis 44:34).

So, what do you do, when it’s just you, and there is no God in sight to tell you what to do?

What will you do when it’s all up to you to figure out how to get through life’s pain and hard choices, too?

What will you do to find out what is true when there is no God to make it easy for you?

Joseph howled. He cried from deep in the pit at the bottom of his anguished soul. In that moment, he may have realized the price of loneliness, of giving up on sharing his life with other people, no matter how imperfect they may be.

Joseph ripped off the mask and showed himself to his brothers, who were, frankly bewildered. In that moment (Genesis 45:2), Joseph decided that he would let go of his pain, his anger and his desire to hurt, hurt, hurt his hurtful brothers. In the dark place within him that felt so unloved and so robbed, he decided to make his own love, grow his own hope, and find his own way of making things right.

Jospeh decided that, even if there were no God around to tell him what to do, he would behave as if there was. He would himself stand in the place that God had left empty and create his own light out of the inky nothingness. For the sake of life, for the sake of love, for the sake of what’s right, Joseph would fill the void.

And this, you know, this is us, too. Right? We don’t live at the beginning of Genesis, either, when God was right at the center of it all, pulling the strings and making the miracles fall like fruit from a tree. God, for us, is not that at all. God for us is less than a rumor. God has pulled into the shadows so tightly that we only catch small glimpses of God in miraculous sunsets and the cries of newborns. God is still here, but God feels so very far away when we need answers to life’s struggle, challenges and pain.

So, what should we do, when we know it really is just us? The choices are right there. Succumb to the darkness, or make our own light. There are days, we admit, when it feels it’s all pointless and morality is a fantasy. We want to put ourselves first and let others taste the pain. After all, what point is there is being a sucker in a world that doesn’t care?

Or, we can be Joseph. We can wake up from the darkness with a howl and say, “Not today. The darkness of despair and meaninglessness is not going to win today. Today, I’m letting go of my hurt feelings. Today, I am admitting the scars I carry with me, but I’m also going to start filling the emptiness by living the love I know is in me. I’m gong to nurture my grown-up hopes. I’m going to make things right, no matter how wrong they may be right now.

“And, if there is no God around to tell me what to do, I will behave as if there is.”

It’s up to us. We can choose to try to increase the light, to do what’s right. We can choose to forgive, to reject our darker impulses, admit our mistakes, love people as if our hearts have never been broken, live with our pain but not allow the pain to control us, and to be imperfect beings who, despite our imperfections, take responsibility for building a better world.

It’s Yom Kippur. It’s the day to decide. Which choice will we make? If God is no longer doing it for us, will we make our own light out of the nothingness? Because, I have to tell you, it’s just us. God is not giving us any more instructions. God has decided to let us figure out for ourselves how to let go of our pain and create our own love. The choice is ours now to do what’s right.

God is waiting. Let’s decide. What will we do?

G’mar chatimah tovah. May you be sealed for a good year.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed