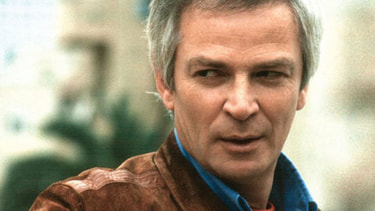

Israeli singer/songwriter Arik Einstein (1939-2013)

Israeli singer/songwriter Arik Einstein (1939-2013) When you are a rabbi, even a Reform rabbi, people tend to assume that you must have grown up in a religious household. It’s a curious assumption. I have to tell you, though, that, in my experience, it’s rarely true. Most of the rabbis I know – even many of the orthodox rabbis I know – did not grow up in homes that they thought of as religious when they were growing up. I certainly did not.

I grew up in a home that had a strong sense of Jewish identity. It would have been difficult for us not to. My mother came to the U.S. as an infant from France when her parents fled Europe. It really wasn’t possible for my mother’s family not to have a strong awareness of being Jews. The Nazis made sure of that. Yet, when they arrived in America, my mother’s family did not hold on to traditional Jewish observance for very long. My grandmother did not keep a kosher home. My grandfather’s idea of a house of worship was the New York Metropolitan Opera.

My father’s family was also strongly Jewishly identified. My grandfather on that side was a national officer of Alpha Epsilon Pi, the largest Jewish fraternity in the world, and he was a national officer of the American Jewish Congress. Being Jewish was more than a cultural afterthought for my father’s family, but they were not what most people would regard as “religious.” They did not attend Temple frequently. They did not observe Shabbat on anything like a regular basis.

Likewise, the household I grew up in was not religiously observant in the conventional sense. We went to Temple on the High Holy Days and my sister and I went to Religious School. But I do not remember a single time in my entire childhood when we lit Shabbat candles at home. There may have been a Hebrew Bible on one of the bookshelves in our home, but there was not another single religious book anywhere in the house – until I received a few as bar mitzvah gifts.

So, what was it in my childhood that got me excited about being Jewish – enough that I decided to become a rabbi later in life? I’ve asked myself that question many times. The answer that makes the most sense to me now is this: My father always told me that part of my job in life was to, "Make the world a better place than it was when you came into it." He used that phrase many times throughout my childhood. It never even occurred to me when I was a child that it was Jewish. But it sure was.

One of the most famous teachings in rabbinic tradition about making the world a better place comes from Pirke Avot. It says, לֹא עָלֶיךָ הַמְּלָאכָה לִגְמֹר, “It is not your duty to finish the work,” וְלֹא אַתָּה בֶן חוֹרִין לִבָּטֵל מִמֶּנָּה, “but neither are you free to neglect it” (M. Avot 2:16). Judaism teaches that none of us is expected to fix everything wrong with this world, but, nonetheless, we all have an obligation to do what we can.

I’m thinking today about my father teaching me that lesson because my family celebrated his 80th birthday this week. I’ve been reflecting on the impact he has had on my life and how it shaped me from an early age.

In college, I was an activist. I mean, it says on my college diploma that I majored in Theater, but the truth is that I majored in political activism. I worked on campaigns to get my college to divest from companies doing business in South Africa during Apartheid. After graduating college, I went to work for a national environmental advocacy group.

All the time I worked on these campaigns, I thought about what my father taught me when I was a kid. I remembered him saying, "Your job is to make the world a better place than it was when you came into it.”

It was only after I had been doing that work for about eight years out of college that I started to notice that many of my contemporaries in social change organizations left to do other things with their lives. A lot of them became lawyers. Some went back to academia to become college professors. Some just went on to careers in fields that had little to do with social change – writers and bookkeepers and marketing directors. One friend became a professional glassblower.

I did not resent their choices. I could not blame them. Working to make the world a better place is exhausting. It does not pay well. You don’t always notice that it’s making any difference at all. In a way, I was jealous of my friends who went to do other things with their lives. I even wondered: What’s wrong with me that made me think that it’s my job – somehow – to change the world?

That’s when it hit me. The thing that made me think that I had to work for social change was my Jewish identity. It was the Judaism I was exposed to as a child that taught me that being Jewish meant that I was part of a bargain with God – a bargain we call “the covenant.” The deal is this: We are expected to do mitzvot – actions that bring kindness, justice, compassion and holiness into the world. In exchange for fulfilling the obligation to do mitzvot, God rewards us by – giving us more mitzvot to do.

That is, in a nutshell, the Jewish notion of why we are here and what our lives are all about. Our purpose in life is to do things that bring the world closer to what God intended the world to be when God created this reality and said, “This is very good.” Our job is to make it true – to make the world good.

When I realized that my drive to make the world a better place came from being a Jew – that was the moment that I started to get serious about learning as much as I could about Judaism. I haven’t stopped since. Apart from being a husband and father, it has become the most rewarding thing I have ever done in my life.

Learning about Judaism has helped me to understand my childhood and my life in ways that did not occur to me as a child. My family and I did not think of ourselves as “religious” when I was growing up, but maybe we were more religious than we knew. We were living Jewish values in a way that was deeply embedded in our identity. We not only believed that it was our job to change the world, we believed that changing the world was possible, that it was necessary, that it was something that we could see happening in the world around us, if we only paid attention to it.

Not everyone shares that kind of optimism about the world, but, I think, it is a belief that is intrinsic to being a Jew. Jews are addicted to hope – the belief that no matter how terrible the world may be, no matter how horribly people may treat each other, there is always the possibility that everything can be turned around. This world can be transformed into a paradise.

I’ll tell you where I see Jews who are filled with that optimistic belief. I see it in community centers and social service agencies. I see it at the State House. I see it in our Temple community and wherever people are helping others.

I also see it in the state of Israel. Think of it: in response to the greatest tragedy ever suffered by any people in human history, the Jewish people pulled themselves out of their misery and built a nation. In their ancient homeland that had been little more than a desert for centuries, they built an oasis, a miracle. Now, Israel has a lot of problems and there is much about Israel that concerns us. But, there are not very many other peoples in the world that could do what the Jewish people have done in reclaiming their ancient homeland. We did it. Jews never seem to despair or tire of trying to make the world a better place.

The Israeli musician and composer Arik Einstein sang about that spirit. His name may not be too well known among American Jews, but, to many Israelis, Arik Einstein is the poet who taught Israel what it means to be an Israeli.

What did Arik Einstein say in his songs that so perfectly captured the essence of Israel and of being a Jew? His most famous song, Ani v’Ata, says it all:

You and I change the world,

You and I, and then all will follow.

You and I change the world.

Others have said this before me,

But, that doesn’t matter.

You and I change the world

You and I will try from the beginning.

It will be hard for us, but that doesn’t matter,

It’s not so bad.

Others have said this before me,

But, that doesn’t matter.

You and I change the world.

You and I change the world,

You and I, and then all will follow.

You and I change the world.

Others have said this before me,

But, that doesn’t matter.

You and I change the world

This is what I love about being Jewish. It’s that casual certainty that we have a job to do. It’s a hard job, but that doesn’t matter. After all, if you have been given the whole world as a present that you did not even have to ask for, is it such a big thing to be expected to leave it a better place than you found it?

No. It would be rude not to. And, besides, that’s the deal that we have going with God. Just like my dad taught me.

Shabbat shalom.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed