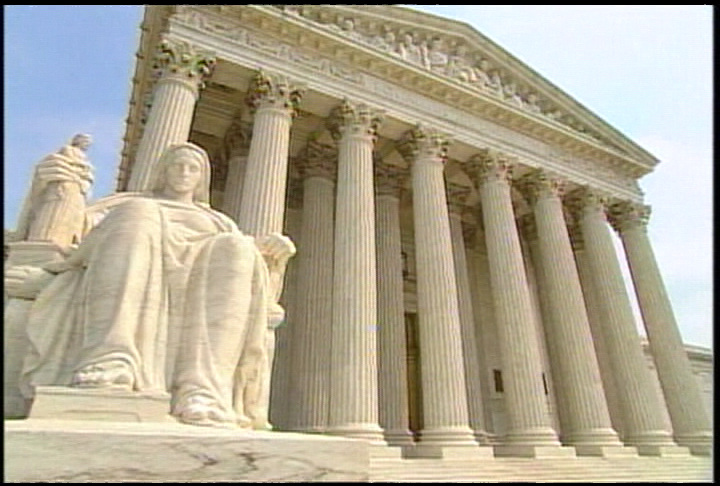

| The Supreme Court ruled this morning that the Affordable Care Act (a.k.a., "ObamaCare") is constitutional. The Court's decision says that Congress did not exceed its powers under the U.S. Constitution by saying that every American must be covered by a health insurance policy or pay into a national fund to provide healthcare coverage for others. |

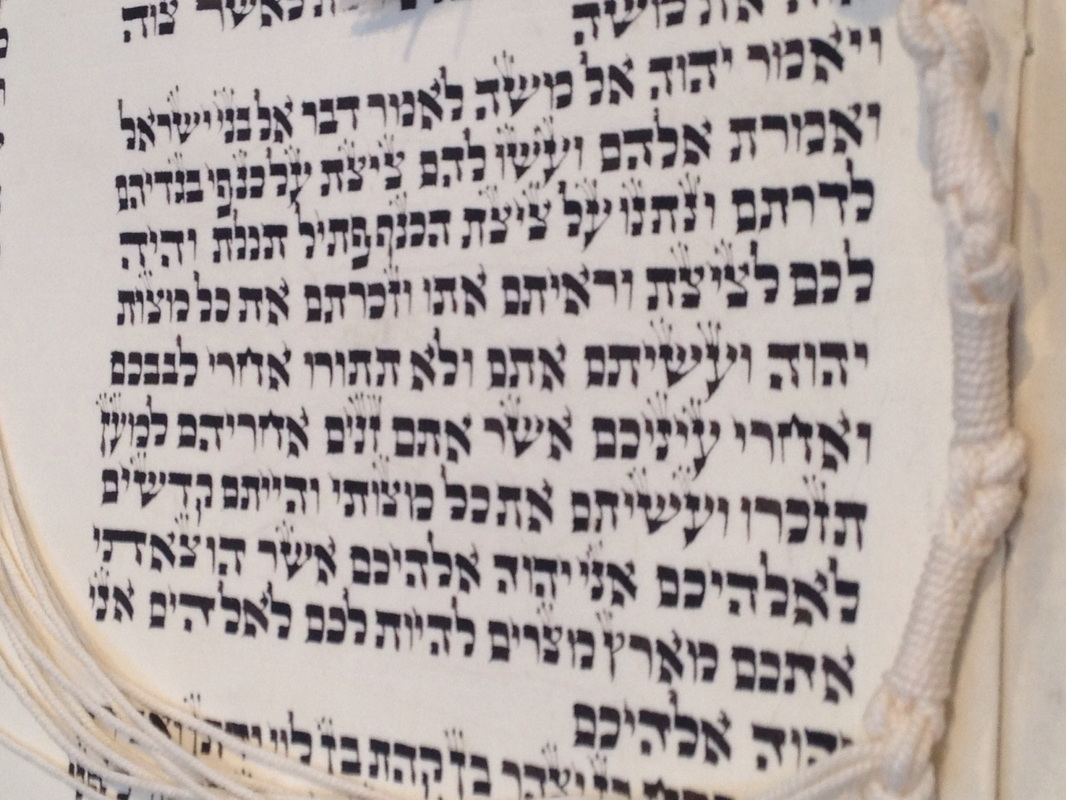

It is, somehow, appropriate to the national debate about healthcare that the classical rabbis’ discussion of the topic begins with a passage in the Torah about people fighting. In the book of Exodus there is a case that involves an altercation between two people. The Torah states, “When people quarrel, and one of them strikes the other with a weapon or with a fist, and the stricken person does not die, but falls ill and must take to bed—if the stricken person eventually rises and is able to go about outdoors on a staff, the assailant shall be cleared, except that the assailant must pay for the stricken person’s loss of time and he must surely heal him” (Exodus 21:18-19).

In context, it is clear that the Torah means that the assailant must pay the medical expenses of the person he has injured. The classical rabbis interpreted the verse in this way, but they also expanded its meaning. In the Talmud, the verse is taken as proof that we have not only the right to treat injury and disease, we are commanded to do so (B. Berakhot 60a, B. Bava Kama 85a).

Most Jewish authorities accept and extend this obligation. In most circumstances, physicians are required to do everything in their power to heal people in need, regardless of the financial means of their patients. Maimonides, the great medieval philosopher, who was also a physician, stated it this way: “The doctor is obligated by law to heal” (Sefer Ha-Ma’or, Nedarim 4:4).

What is more, Jewish tradition does not see the obligation to heal as being solely the responsibility of physicians. The Talmud states that a person is forbidden to live in a place where there is no doctor (B. Sanhedrin 17b), and that the obligation to provide medical care for the members of ones family is of the same degree and kind as the obligation to provide food (B. Ketubot 52b).

The passage in Exodus that requires an assailant to pay the medical expenses of his victim is also used by the rabbis as evidence that doctors should charge for their services. However, given the importance of making medical care available to all, the rabbis do place restrictions on how much health providers may charge. The Shulchan Aruch, the most important medieval collection of Jewish law, states, “If one has medications, and another is sick and needs them, it is forbidden to raise their prices beyond what is appropriate” (Yoreh De’ah 336:3).

However, the rabbis state that the ideal situation is one in which the community creates a fund of voluntary donations that are used to provide medical care for those who are too poor to pay for it themselves. The Talmud praises the model of a physician named Abba who set up a box for communal donations outside of his office door: “He had a spot outside to put coins. Those who had put some in, but those who did not have could come in and sit without being ashamed” (B. Ta’anit 21b).

The emphasis on avoiding shame is a telling and a typical concern of the rabbis. One of the central principles of Jewish tradition is respecting the dignity of each human being. The rabbis equate shaming people with shedding their blood. We must do more than merely provide for people's material needs, we must do so in a way that honors them as beings created in the image of God.

It is not difficult to recognize how the healthcare system in the United States today fails to uphold the principles of the Talmud. Our society has not taken upon itself the obligation to heal those who are in need. Every day, untold thousands of Americans must choose between paying for healthcare or meeting other basic needs for themselves and members of their families.

Also, the American system does not put any checks on the cost of healthcare. Hospitals, pharmaceutical companies and doctors charge exorbitant amounts for even routine medical services to the uninsured.

Most troublingly, the American system of providing healthcare does little to respect individual dignity. Anyone who has ever spent hours on the phone trying to resolve a dispute with a health insurance company (I can't be the only one) knows this. Anyone who has had to suffer the indignity of pleading with an insurer, a hospital or a medical professional for services they cannot afford knows it even better.

I cannot argue that the Affordable Care Act is the best way to answer these ills, that it is what the Talmud mandates, or even that it will be effective. I can say, though, that Jewish tradition says that we have an obligation as a society to try to do a better job than we are doing now. The Supreme Court today said that the federal government has the authority to fix a broken system by creating a mandate for every citizen to do their part to provide healthcare for all. I believe that that mandate is entirely consistent with what Jewish tradition expects of us.

Fixing our broken healthcare system is not just a matter of helping the needy—although, that is an important aspect of it. Providing healthcare is a moral necessity that we all owe to each other. We all deserve to be treated with dignity and compassion. All of us are mortal. We all grow sick and we all, someday, will die. Part of what makes us truly human is our commitment as individuals and as a society to make sure that, when that happens, the care and comfort we need will be there for each of us, regardless of how wealthy or poor we may be.

Other Posts on This Topic:

The Joyful Imperative to Interpret

Tazria-Metzora: The Torah of Reproductive Health Care

On Contraception, Religious Freedom and Joy

RSS Feed

RSS Feed