| Modern people do not like authority much. We always have to have a reason why we should allow someone else to make decisions on our behalf, tell us what to do, or have any measure of control over us. We’re always asking, “Who made you king?” And maybe it is not just a modern issue. The story in this week’s Torah portion is about a man named Korach who says to Moses and his brother Aaron, “All of God’s people are holy. What gives you two the right to rule over us?” (Numbers 16:3). |

That’s the end of that argument.

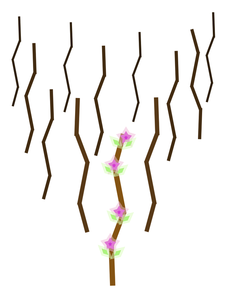

But there is a kind of postscript at the end of the story of Korach’s rebellion. After the revolt ends, God instructs the leaders of the twelve tribes to each place their staffs—dead pieces of wood, really—into the sanctuary where God’s presence rests. One of the twelve staffs, the one that belongs to Moses’ brother Aaron, sprouts blossoms and even grows flowers and almonds as a sign that he has been divinely chosen to carry God’s authority.

What Aaron says, goes. Why? Because God says so.

What does that have to say to us in our struggles with the idea of authority? God isn’t sending us any miracles today to tell us whom we have to obey. (It probably wouldn’t work, anyway. We still wouldn’t obey.) What should this story mean to us?

The reality is that we do need authority, much as we try to escape or avoid it. Society just could not function if each of us was completely free to decide how to behave. Taxes would never be collected, crimes would never be challenged, rules would never be adopted, and communities would never be formed if no one would submit to the authority of anything outside of themselves. As the philosopher Thomas Hobbes put it, life without authority would be, “solitary, poor, nasty, brutish, and short.”

What I like about the story with the sprouting staff—especially after the wrathful story of the earth swallowing Korach whole—is that it affirms that authority equals life. Authority is symbolized by a dead piece of wood bearing fruit, reminding us that without submitting ourselves to the authority of something outside of ourselves, we’re all dead meat.

Reform Judaism is built on the idea of autonomy. Each Jew, in the thinking of Reform Judaism, has the autonomy to choose the forms of observance that are most meaningful to him or her. Reform Judaism says: “You find the symbolism of wearing a tallit on Shabbat to be meaningful and spiritually fulfilling? Great! Wear a tallit. If a tallit doesn’t do much for you, though, don’t wear it. It’s up to you.” Each of us, according to this ideal, has the power to create our own Judaism.

But, wait just a second…If each of us can create “our own Judaism,” then what is Judaism? Is Judaism just what any Jew decides Judaism should be? What if someone wants Judaism to be Buddism? What if someone wants Judaism to just be eating bagels on Sunday morning? What if someone wants Judaism to be nothing? Can Judaism be nothing?

Reform Judaism does have limits. Judaism requires some authority to maintain its distinctiveness, its boundaries, its ethics and ideals. Reform responds to that need, not by knocking people over the head with a set of dead rules, but with the sweet taste of the almond and the fragrance of its flowers.

Authority does not have to be punitive. Reform Judaism, in general, prefers to maintain its boundaries by accentuating that which is attractive and distinctive about Judaism. Reform Judaism emphasizes the beauty of Judaism’s language, rituals, and culture; the intellectual appeal of its ideals and values; the warmth and openness of its communities; and, most of all, its pathways to meaningful encounter with God.

The story of the sprouting staff challenges us, as Jews and as human beings, to ask what authority we place over us in our lives. Whom do we serve? Our own desires? Our fears? Our jobs? Money? Or, do we accept the authority of something higher—values, ethics, devotion to family and community, God? Are we ruled by the stick that threatens to chase us, or are we ruled by our own pursuit of the sweet scent of values that affirm life?

Other Posts on This Topic:

Korach: Walking into Trouble's Tent

Nitzavim-Vayeilech: Is There Such a Thing as a Religious Reform Jew?

Beha'alotecha: Eldad and Medad

RSS Feed

RSS Feed