These origin stories serve, in part, to say something about the character and values of heroes, of nations, and of the world. Superman fights for the well-being of the world because he knows what it feels like when your world is destroyed. The Romans saw themselves as noble survivors because they believed themselves to be descendants of warriors who fought for survival.

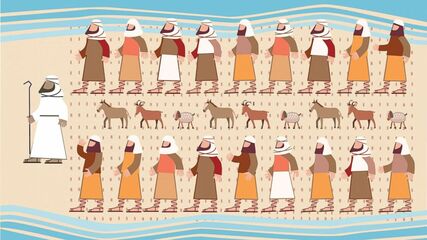

Passover is the great story of the origin of the Jewish people. We celebrate the holiday by retelling the story of how we were slaves and how God saved us. We recite for our children the legend of God's plagues against our captors and how God performed miracles to make us God's own people. Our story, too, serves to tell us something about who we are, about our values, and about the world we aspire to create.

Here are some of my thoughts this year about what our origin story is supposed to teach us about ourselves and the world:

• Isn't it odd that we see ourselves as slaves in our origin story? Most civilizations tell stories about how their founders were brave soldiers or noble kings. We tell a story about how our founders were helpless servants to mighty Pharaoh. The story describes how we complained and griped all the way to freedom. At its essence, our origin story warns us against arrogance and hard-heartedness. It reminds us that, without God's help, we are nothing. It also reminds us to have compassion for people who are oppressed and helpless. We know that experience, too.

• The traditional Haggadah makes very little mention of Moses. We do not want to tell our story as the tale of one great man and credit him for our victory. The story we tell about ourselves is that no one human being has ever been our savior. Instead, we look to God and we look to ourselves as a collective nation for our redemption. Judaism, as a religion, is highly suspicious of the human tendency to turn great people into heroes, and to turn heroes into gods. We don't want to elevate any human to the status of a god. We have seen how the Pharaohs of the world quickly turn despotic, and how those who worship false gods become passive and cruel.

• In our origin story, the final chapter of the story is never told. By the end of the Seder, the Israelites are still a ragtag mob that has just witnessed the redemption at the Sea of Reeds (or, the Red Sea). We stop the story before we can get to Mount Sinai and the Ten Commandments. There is even a self-conscious incompleteness to the story seen in the four cups of wine we drink. Each cup represents a promise that God made to us: "I will bring you out of slavery in Egypt," "I will save you from their bondage," "I will redeem you with great power," and "I will take you as My people" (Exodus 6:6-7). However, there is a fifth promise in the biblical narrative: "I will bring you to the land which I promised" (Exodus 6:8). That unfulfilled promise is represented by Elijah's Cup, the cup from which we do not drink. The symbolism of the seder reminds us that our journey is incomplete. There is much that we still have to do to make God's promises true in the world.

As you experience the seder this weekend, consider what our story says about us. Think about what our first lesson is trying to teach us. We are not Romans who live to conquer and endure. We are not superheroes endowed with magical powers. In the story we tell about ourselves, we are human and deeply flawed. We are friends to those who are powerless and suspicious of those who are powerful. We are on a journey that is far from complete, but we are asked to be a part of it and to help write the next chapter – the one that starts today.

Other Posts on This Topic:

The Great Sabbath, Elijah's Cup, and the Unkept Promise

Matzah and Chameitz

RSS Feed

RSS Feed