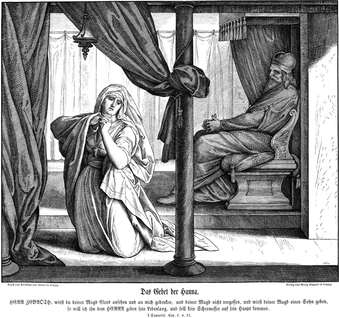

"Hannah's Prayer," an illustration from Die Bibel in Bildern by Julius Schnorr von Carolsfeld (1853).

"Hannah's Prayer," an illustration from Die Bibel in Bildern by Julius Schnorr von Carolsfeld (1853). The Haftarah we will read at tomorrow morning’s service includes one of the most moving stories of prayer in the Hebrew Bible. The story comes from the book of Samuel and it tells of a young woman named Hannah whose life was filled with love and filled with sorrow.

Hannah was one of two wives of a man named Elkanah. We hear in the story that Hannah was Elkanah’s favorite wife, but we also hear that she was barren – she could not bear children. In contrast, Penninah, Elkanah’s other wife, was the mother of many sons and daughters. We sense immediately that this is a family in pain. There is a beloved wife who watches in grief as she sees another woman bearing children for the man she loves. There is an unloved wife who bears children for a man who is in love with somebody else.

Each year, Elkanah took his family to the Temple in Shiloh to bring the first fruits of their harvest as an offering to God. Each year, Penninah took the opportunity to make Hannah feel inadequate for her inability to bear a child. Peninah would say, “Look, Elkanah has given me so much food from the harvest to share with my children, but poor, childless Hannah only has her one meager portion.”

Hannah just couldn’t take it any longer. One year, when at Shiloh, she entered the Temple and stood before the altar of the God of Israel. Tears ran down her cheeks as she silently prayed for a child — a child who would fulfill her dreams of motherhood and who would end her years of humiliation. Her lips trembled as she quietly made her petition to God.

The priest, Eli, saw this young woman with a ravaged face prostrate in the Temple. He saw her clothes, rumpled from lying on the ground. He saw her mouth opening and closing noiselessly. All he could think was, “Who has let this drunken harlot into my Temple?” Eli said to Hannah, “How long will you be a drunkard? Get rid of that wine you’ve been drinking!”

Hannah, startled by the priest’s accusation, turned to Eli and protested, “Oh, no, sir! I am no drunkard. I don’t drink wine or strong drink at all! The only drink I have poured is my own heart, which I am opening to God in prayer. Please, do not take me for some kind of a fallen woman. All this time I have only been praying a prayer of my anguish.”

Eli recognized in Hannah’s tears that she was not what he had first imagined. He regretted how quickly he had judged her, and now spoke to her with kindness. “Well, then. May you go in peace. And may the God of Israel grant the request that you have made here.”

The Bible tells us that Hannah’s prayer soon was answered. She returned to her home and became pregnant. Her son would grow up to be Samuel, the great prophet who anointed both King Saul and King David, Israel’s first two kings.

On one level, the story could be read as one in which Hannah makes a bargain with God — “If you give me a son, I will dedicate him to You.” God takes the deal and rewards Hannah with a son. It is a familiar story and there are many like it in Jewish tradition and in folklore from around the world. Samuel is the “miracle baby” who is destined for greatness. However, like many legends, it should not be read only on that literal level alone.

The point of the story is not that, if you pray hard enough, God will fulfill your lofty dreams. If that were true, then the opposite also would have to be true — if you have not received the things in life you deeply desire or need, it must be because you are not praying hard enough. Imagine what a message that would send to the many "Hannah"s in the world today – women who struggle with infertility.

The story is about something deeper. It is about the human need to express ourselves to eternity. It is a story about prayer as an expression of our deepest yearnings and highest aspirations. It is a story of how prayer can help us to transform our lives.

There is something within almost all human beings, I think, that makes us want to be heard. We want, as Hannah wanted, to speak the great truths of our lives into the cosmos. Even if we recognize that our lives are brief and our needs are petty compared to the vastness of time and space, we still need to shout out our unique selves and affirm that our pain and our joy, our sorrow and our celebration, our gratitude and our awe all matter and have meaning. That is the essence of what prayer is about.

The rabbis of the Talmud, who lived about a thousand years after Hannah’s time, regarded her prayer as the great example of everything that prayer should be. From the verse that says that “Hannah spoke al libah” — meaning that she spoke “to herself,” or more literally, “upon her heart” — the Talmud says that prayer should be “from the heart,” done mindfully with purpose and intention. In the words of Rabbi Eliezer in the Mishnah, “Anyone who will only pray a fixed prayer has not really prayed to God at all” (M. Berachot 4:4). Prayer must be an act of the heart before it is an act of the mouth.

From the verse that says that Hannah’s lips moved as she prayed, the Talmud concludes that we should make every effort to pray with words. It is not enough to just think about our deepest hopes and highest aspirations, we must actually try to express them in words. There is something about putting our best and most soul-shattering thoughts into words that helps us hear them. Without words, our prayers remain muffled and drowned out by the roar of our busy lives by the internal chatter of our restless minds.

The Talmud observes that Hannah prayed silently so that only she could hear her prayer. The rabbis said that this shows that prayer should not be ostentatious. It does not need to be shouted or turned into a display of false piety. Rather, prayer is a quiet experience, soft enough for us to be able to hear our own souls speaking [B. Berachot 31a].

The rabbis of the first century of the common era had other reasons, too, to like the story of Hannah’s prayer and to make it their model for ideal prayer. The story’s conflict between Hannah and the priest, Eli, resonated with them as a metaphor for Israel’s transition from worship through sacrificial offerings to worship through words.

While the Temple stood in Jerusalem under the leadership of priests like Eli, worshipping God primarily meant bringing offerings of animals, fruits, grains and vegetables to the Temple to be burnt upon the altar. Worshipping God through prayer existed in the time of the Temple, but it was not until after the Temple’s destruction in 70 CE that prayer became Judaism’s exclusive means of worship. The story about Eli, the priest, and Hannah, the woman in prayer, might have reminded the rabbis of Israel’s transition from Temple sacrifices to synagogue prayers.

The rabbis also identified with Hannah because the Bible depicts her just as the rabbis saw themselves — sincere, humble, heartbroken, and loyal to God. Her earnest and heartfelt prayer reminded the rabbis how they viewed spoken prayer not as a pale substitute for sacrifices, but as, in every way, the equal of the sacrificial rites of the Temple.

As the centuries passed, the idea of prayer as a replacement for Temple sacrifices faded. By the medieval era, the Temple and its rites were thought of as a practice from a long-ago time, without much pertinence to their own day. When medieval Jewish thinkers wanted to convince their fellow Jews of the importance of prayer, they hardly ever referred to prayer as a substitute for sacrifices.

Maimonides, the pre-eminent Jewish philosopher of the middle ages, wrote that the purpose of the daily fixed prayers was for our own growth, not for God’s benefit. He said that the practice of prayer trains our minds and hearts in the values that the prayers talk about — love of God, ethical behavior, compassion, reverence and humility. Maimonides saw prayer as a discipline that Jews accept as a daily reminder to live according to the highest values and principles of Jewish belief.

At about the same time, Jewish mysticism developed a different way to think of prayer. To the kabbalists, the fundamental purpose of life is to act as God’s partner in repairing a world that is broken and shattered. Kabbalah claims that we can help repair the universe by becoming aware of God’s hidden presence in the world and releasing that presence by performing mitzvot. According to Jewish mysticism, when Jews pray, we are not just reciting wise and edifying words, we are uncovering the hidden divinity that is within our souls. Prayer helps us to release divine hidden sparks to help repair the cosmos.

By looking at the history of Jewish worship, we see that there is no one way in which Jews have understood prayer. There has been an evolution in Jewish thinking over time and there have been — even in a single age — a diversity of ways for Jews to understand what we are doing when we pray.

And what of us today? What do we believe we are doing when we pray? That’s a difficult question for us to answer because many of us come to High Holy Days services unaccustomed to prayer in any form, or for any reason. We may fall easily back into the habit that many of us have known from childhood of singing along with the congregation or of reading the words in the prayerbook. But many of us do so without a clear answer to the “why” question. Why do we pray? Why is it important to us? Why should we keep doing it?

We have a great deal to gain by finding a way to understand prayer as a meaningful experience. I believe that we need prayer, as much as any generation before us, to express ourselves and the meaning of our lives to the cosmos. I believe that we can improve our lives by find a discipline of prayer that works for us.

Here is a way of thinking about prayer that I believe can work for us. In the twenty-first century, prayer can be our way to find our way back to who we really are in a society that tries so hard to make us into something else.

We are living in an age in which we are bombarded by messages about what we are supposed to want. Whether we are told to want money, power, ice cream, an iPhone, or a really killer set of abs — it’s hard not to feel confused in a society that seems obsessed with the trivial and in which it is so difficult to find clear statements of what is truly meaningful and fulfilling in life. As a result, many people feel disconnected from their values and many struggle to find a higher purpose in their lives.

Prayer for us can be a way to quiet the voices that tell us what we should crave, and focus our attention, instead, on the things that really make life fulfilling: loving relationships, meaningful work, a sense of purpose, dedication to our values, and a sense of wonder for the miraculous world around us.

Let me give you some specific examples of the prayers in our tradition that help us to do this. We have prayers in Jewish liturgy that are about recognizing our physical, bodily needs. In the morning service, we recite blessings for getting up out of bed in the morning, for getting dressed, and even for the ability to use the bathroom. We use prayer as a way of staying in touch with the sanctity of our bodies and our physical needs, which are the foundation for all of our other needs.

We also have many prayers in Jewish liturgy that are about the need to bring justice and righteousness into the world. These prayers seem designed to lift our thoughts beyond our physical needs and into an awareness that we live in a moral universe that is shaped by principles and ideals. These prayers energize our desire to make the world a better place for ourselves, our families and communities. They remind us to live for principles and values, not just for fulfilling our cravings and desires.

Many of our prayers call us to think about our gratitude for the miracle of just being alive. These prayers turn our thoughts away from our momentary desires and into the realm of awe and reverence. We reflect on how we fit into the big picture of a world that we did not create. We open our minds to the obligations that accompany the gift of our existence — what we owe to others and what we owe to ourselves. In prayer, we stand before God and feel ourselves to be a small part of an eternity that stretches beyond our imagination. In that moment, we can rediscover the comfort, joy and equanimity of belonging in the universe. We remember that the meaning of our lives is part of the universe’s meaning — that our lives matter.

Now, I want to ask you something. How would your life change if you took the time on a regular basis to remind yourself — no matter how crazy the world around you may get — that there is a meaning and purpose to your life? How would you, as a person, change if you regularly and intentionally reminded yourself that your life is actually a mission to honor your highest values, to make the world around you a better place, and to lovingly care for others? How would the way you think about yourself change if you regularly took the time to develop a sense of inward peace?

This is why, I believe, we can benefit from developing a prayer practice in our lives — it has the potential to awaken our hearts to the things that really matter to us. It can help us join with others to make our community a healthier and kinder place. It can make us happier.

Hannah offered her prayer for a child in a private and spontaneous moment. She had no need of a prayerbook to find the right words to say to God. All she had to do was to open her heart and allow her powerful feelings to flow out of her. That quiet place of the soul where our deepest yearnings live is the place that we can touch and release in prayer.

Prayer does not require a prayerbook or a prescribed formula to work, but many people find that fixed prayers help them find the words that express what they feel in their hearts. Prayer can happen in the synagogue during regular worship times, or it can happen while we are walking in the woods. It can even happen while we are standing on the check-out line in the supermarket. All it takes is the determination to listen to the yearnings of our own souls in a focussed and disciplined way.

If you are feeling right now that you are unequal to the task of taking on a prayer practice. If part of you is saying, “Yes, that sounds like it would be good for someone else, but I’m not that kind of person,” I want to let you know that it doesn’t really matter what kind of person you are.

Psalm 69 contains a verse (v. 14) that appears at the beginning of the traditional morning service: “Va’ani t’filati l’cha, Adonai.” Literally, the verse can be read to mean: “I am my prayer to You, Adonai.” The verse reminds us that all we can really offer when we pray is ourselves — I am my prayer – and that is enough.

We do not need to pretend to be someone else when we pray. We do not need to approach God as if we were saying, “God, I’m not really a good enough person to be talking to You. I’m not religious enough; I don’t believe in You enough. I’m actually kind of embarrassed just to be talking to You.” None of that is necessary, thank God. If it were, no one would ever bet able to utter a single word of sincere prayer.

“Ani T’filati,” “I am my prayer,” means that your best prayer is the one that comes from you just as you are. You are already good enough. You don’t have to be someone else in order to express your pain, your joy, your hopes and your disappointments to the cosmos. Doing so, just as you are, can do for you what it did for Hannah. It can make you feel heard. It can make you feel that your life matters, that your sorrow has dignity, and that your gratitude for what life has given you can help you better enjoy life. It can bring you a sense of inner peace when you are surrounded by turmoil and it can give you strength to face life’s toughest moments.

I am my prayer. I am the very thing that I need to say to eternity, and I feel that eternity answers back to me in the quiet and moving moments of my life.

This year, at our High Holy Days services, we are using a new prayerbook, Mishkan HaNefesh. It is, I think, an opportunity for each of us to re-evaluate our relationship to prayer. Maybe this is the first time you have sat in a synagogue using a prayerbook that talks about God in a way that seems approachable. Maybe you miss the heightened language of “Lord,” “King of the Universe,” and “Blessed art Thou.” Or, maybe you are ready to think of prayer as being more like a poem than like a rigid legal formula. Maybe this prayerbook has you ready to think about how you can be your own prayer.

As we go through the Days of Awe together between now and the final shofar blast of Yom Kippur, I would like to invite you to try praying like you’ve never prayed before. Pray as a way of uncovering the things in life that you are truly grateful for. Pray as a way of discovering your sense of your life’s mission and purpose. Pray, like Hannah did, as a way of openning up the places where you feel wounded and in pain. My hope for you, is that your prayer be a source of meaning, joy, discovery and healing.

This Rosh Hashanah, make the choice to include some kind of prayer practice in your life on a regular basis. It could be a moment to look up to heaven while you’re waiting on the grocery check-out line just to say, “Thank you.” It could be including a moment of gratitude for your food before you dig in. It could be a moment to sing Shema with your child before tucking her or him in at night. It could be a moment to hope for the wellbeing of the people you love as you lie down to sleep at night.

Try it. You might find that it eases your pain, gives you a sense of purpose, helps you feel heard in a noisy world. It may make you feel like you can finally hear yourself. And, it might make you feel happier.

L’shanah tovah tikateivu. May you be inscribed for a good year

RSS Feed

RSS Feed