In April of 1963, the month in which I was born, eight notable white clergymen in the city of Birmingham, Alabama, wrote a public letter in objection to what they saw as the racial tensions rising in their city. They wrote:

“We are now confronted by a series of demonstrations by some … directed and led in part by outsiders. We recognize the natural impatience of people who feel that their hopes are slow in being realized. But we are convinced that these demonstrations are unwise and untimely…

“We also point out that such actions as incite to hatred and violence, however technically peaceful those actions may be, have not contributed to the resolution of our … problems.

“We urge the public to continue to show restraint…

“We further strongly urge the Negro community to withdraw support from these demonstrations, and to unite … in working peacefully… When rights are consistently denied, a cause should be pressed in the courts and in negotiations among local leaders, and not in the streets. We appeal to both our white and Negro citizenry to observe the principles of law and order and common sense.”

To me, reading this letter, I can’t help but think about the calls I hear today criticizing the protests that are spreading across our country in response to the killing of George Floyd four months ago or the shooting of Jacob Blake four weeks ago. There is a similarity in the focus on the violence that sometimes comes with large-scale public protests. There is a similarity in the reassurance that the legal system and negotiations are a better way of addressing racial tensions than public protests. I know that there are some people listening to this sermon who agree with that approach.

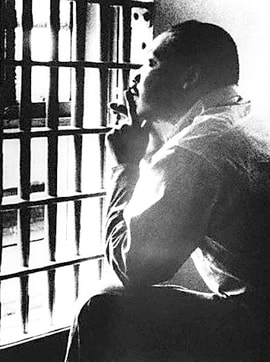

The letter was written in response to marches and sit-ins organized by a 34-year-old Black minister from Atlanta named the Rev. Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. King wrote a letter back to the signers of this statement while he was incarcerated for his role in the demonstrations. King’s response is known as the “Letter from a Birmingham Jail.” It was published across the United States and became a central text of the civil rights movement.

King wrote kindly to his eight fellow clergymen and recognized their good intentions, but he said that their calls for restraint and negotiations, rather than demonstrations and direct action, missed the point of what was actually going on.

King asked the clergymen why their letter had no words of rebuke for the bombings of Black churches, the legal exclusion of Black people from white-owned businesses, the racial segregation of public accommodations, the brutalization of Black people by the police, the grossly unjust treatment that Black people received in the courts, and the way that “the city's white power structure,” in King’s words, “left the Negro community with no alternative.” How, he wondered, could they ask him to wait, when Black men and women had tried using the courts and negotiations to no avail. King asked them to recognize that the time had come for more aggressive action, even if it made some white people feel uncomfortable.

Nowadays, Martin Luther King, Jr., is regarded as an American icon of justice and the struggle for racial justice. We celebrate King’s birthday as a federal holiday. Consider, though, that King was not treated with that kind of respect during his lifetime. Far from it. The Director of the FBI publicly called him, “the most notorious liar in the country.” Even after Dr. King won the Nobel Peace Prize for the non-violent movement for racial justice, 75% of Americans said they disapproved of him.

The criticisms of King then were much like the criticisms against the Black Lives Matter movement today. King, too, was regularly called a “Marxist,” “anti-white,” and accused of fomenting a “mob mentality” that would lead to violence. Today, Black civil rights protestors have even been called “paid anarchists” who are “trying to destroy America.”

Just as King charged that his critics failed to acknowledge the realities lived by Black people in 1963, today’s critics of today’s civil rights movement generally fail to acknowledge the experience of suspicion, intimidation and violence that today’s Black Americans have with police. We all abhor the violence and looting committed at public protests by people with a wide range of motives and ideologies. But, like the clergymen who wrote their letter about Martin Luther King in 1963, we need to make sure that we are not missing the point of what is actually going on.

According to a recent poll from the non-profit, non-partisan Kaiser Family Foundation, 41% of Black Americans say they have been stopped or detained by police because of their race. Twenty-one percent of Black adults say they have been a victim of police violence – pushing, shoving, beating, killing. One in five. Think about how that makes it feel to see a cop in America if you are Black.

According to the independent non-profit organization, Mapping Police Violence, more than 750 people have been killed by police in the United States so far this year. And the people who are being killed are, far out of proportion to their numbers in the population, Black people. A Black person is three times more likely to be killed by police than a white person. Black people are also 30% more likely than white people to be shot by police when they are unarmed.

Police don’t kill Black people as often as they do because Black people are bad. Police kill Black people because of an ingrained bias against Black people in American society that presumes them to be dangerous, untrustworthy and criminal. It is a bias that can be traced back for centuries, beginning with nearly two hundred fifty years of slavery and another century of legally enforced racial segregation after that. It is a bias in which Black people have been regarded and treated as inferior to white people.

Bias and discrimination against Black people is not a problem with American police. It’s a problem with American society. It’s a problem with all of us, but it is not a problem we cannot solve.

This morning, we heard the prophet Isaiah warning us about treating other human beings shamefully – true today as it was more than 2,500 years ago. Isaiah said that instead of just fasting on a day like today, we should be working to “break the bonds of injustice” (Isaiah 58). God wants that from us far more than our prayers on Yom Kippur.

In America, in the year 2020, we need to hear Isaiah and recognize that it is far past the time when racial bigotry should be acceptable. Yet, it has become such an integral part of our society that most white people don’t even notice it. It’s like the air we breathe.

How many white people take it for granted that they can walk in an unfamiliar suburban neighborhood without being followed, interrogated or searched by law enforcement because they “look suspicious”? How many white parents never worry when their teenager goes for a jog in their neighborhood that he will be mistaken for a criminal fleeing a crime scene and be arrested or shot? How many white drivers never consider when they are pulled over for a traffic stop that they might spend that night in a jail cell or worse? Sandra Bland, a 28-year-old Black woman who was pulled over for a routine, minor traffic violation in Texas in 2015, ended up dead in a jail cell three days later.

Black Americans – including Black Jews – take none of this for granted. For many Black people in America, the names George Floyd, Eric Garner, Tamir Rice, and Breonna Taylor play in the back of their heads like a siren every time they see a police officer. If those names are not familiar to you, it is probably because you are white. Just about every Black American adult knows those names and many more – Black people who have been killed by police in just the past few years.

As Jews, we need to hear echoes of such torment from our own history. We have known what it is like to be singled out by an entire society. We have known what it is like to live under law enforcement that presumes us to be criminals. We have known what it feels like to hear politicians talking about us and our people as a “mob” and as an “infestation.”

But our reasons as Jews to stand up against racial injustice are not just about our past. The white supremacy machine that vilified Martin Luther King in the 1960s is still at work today convincing people that there is a conspiracy of lawless, anarchistic People of Color who are set to destroy America – and that Jews are the ones pulling the strings. We cannot afford to be blind to the danger we face when conspiracy theories like QAnon, convince many people that being a good American requires them to be suspicious, and even hateful, of Jews.

So, what are we to do?

Again, Isaiah has some advice for us. The prophet teaches us to befriend the stranger, to see ourselves as the equal of people who are different from us. In the book of Isaiah, God says, “My House shall be called a house of prayer for all people” (Isaiah 56:7), teaching us to count all righteous people of every race and nation as our brothers and sisters.

What is more, Isaiah commands us, “Devote yourself to justice. Aid the wronged” (Isaiah 1:17). We are living in times that test whether we really are willing to pursue justice as our tradition teaches. We must decide whether we will enjoy the temporary comforts of privilege, or recognize and oppose the hatred that has plagued this continent for 400 years. We have the choice of turning a blind eye, or standing as allies with our Black friends who are leading the movement for racial justice.

Let me ask you today to consider doing three positive things for racial justice:

One. Examine your own bias. It is not shameful to distrust people who are different from you. Actually, it’s human. But you don’t want your bias to cause you to treat people unfairly or to presume the worst about them. Take some time to think about the attitudes you were exposed to as a child about race. Question whether those lessons need to be re-examined.

Two. Take some risks to have conversations about race. I’m taking a risk right now in giving this sermon. Am I worried that, as a white person, I might say something “wrong” about the experience of Black people? Of course I am. But it’s a risk worth taking. Our society won’t move forward on the issue of race as long as white people are too scared to even talk about it.

Three. When you hear people say things that seem cruel, insulting or even hateful about people because of their race, say something about it. Every nasty racial joke that gets a snicker instead of a challenge helps to confirm that racial bias is acceptable. Be a mensch. Say something.

Now is the time for us to decide to do what Isaiah asked: Devote yourself to justice. Aid the wronged. Today is the day for us to be on the right side of history and to be allies in the work of making a better world.

G’mar chatimah tovah. May you be sealed for a good year.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed