| This week's Torah portion (Pinchas) picks up in the middle of a story that began at the end of last week's portion. It is a story that frightens us with its praise for a gruesome killing. The women of Moab and Midian sought to defeat the Israelites by wooing their men into the worship of idols. This so enraged God that Moses feared his entire community would be wiped out by the plague God brought as punishment. |

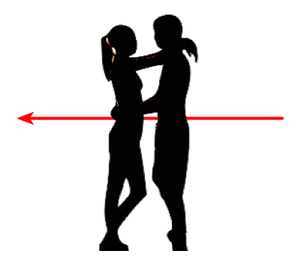

The description is graphically violent and there can be no question about the sexual message of the image. It is as if Phinehas is saying, "If you wish to drive your 'spear' into that foreign woman's belly, I will spear the two of you together, literally." The Talmud even says that the man and woman were copulating at the time Phinehas killed them (B. Sanhedrin 82b). No subtlety there. Phinehas' fury is likened to the fervor of sexual passion.

For this deadly act, Phinehas is rewarded with the priesthood for himself and his descendants. God says, "I grant him My covenant of peace. A covenant of priesthood shall be his and descendants after him forever, for he acted passionately for his God and atoned for the Israelites" (Numbers 25:12-13).

There is no doubt that this is a deeply troubling story on multiple levels. It is wantonly chauvenistic. It condones horrific violence. For now, though, let us look at the central problem of a man who executes two people without any judicial process and, as a result, is treated as a hero. How do we make sense of that?

The ancient rabbis saw that Phinehas' merit was in his fire, his zealous passion to do the will of God. Yet, the rabbis also are wary of such fire. In the Talmud, the rabbis go so far as to say that the man Phinehas killed did have the right to defend himself. Had he killed Phinehas first, the rabbis say, he would not have been guilty of murder.

Phinehas acted outside the law, which can be defended only up to a point, even as an act of righteous fury. Curiously, the Talmud characterizes the case of Phinehas as a unique situation that should never be repeated. "Zealots may kill one who fornicates with Midian women," the rabbis say, "but this is a law that must not be taught" (B. Sanhedrin 82b).

So, what does that say about the Jewish attitude toward zealotry? It is good to be passionate about Judaism. It is good to have a fire within that drives you to a life of Torah. Yet, that fire can become destructive. The rabbis warn against crossing the line that turns zealotry into fanaticism—the point at which we start to use religion as an excuse for shaming, harming, and even killing people.

It is a concern that should not be too distant from our thoughts about religion in the modern world. Whether it is Moslem fanatics who fire missiles to kill innocent civilians in S'derot, or Christian fundamentalists who provoke the murder of doctors who perform abortions, deadly religious fanaticism is alive and well today. In the Jewish community, too, we have seen Ultra-Orthodox Jews attack and persecute other Jews for not being as "pious" as they believe themselves to be.

Jewish tradition says it is wrong. Our texts teach that zealotry, even for a cause motivated by Torah, has its limits. No one should teach that Torah permits or condones harming another for the sake of religious fervor.

And what of Phinehas' reward? Why is he given God's "covenant of peace"?

There may be an answer for that, too. Rabbi Daniel Landes, the Director and Rosh Yeshiva of the Pardes Institute in Jerusalem, suggests that the priestly covenant given to Phinehas is not a reward. Rather, Phinehas was enjoined, from that moment on, to have a relationship with God built only on peace. It is as if Phinehas was told to put down the sword of a soldier and, instead, to take up the peaceful life of priest.

This should be the joyful model for Jewish passion. Our zealotry for God is not measured in how we show ourselves to be holier than others. We find the true fire and ecstatic attachment to Torah and Jewish living in the choices we make that bring our souls to peace.

Other Posts on This Topic:

Pinchas: Five Sisters Who Turned the Key to Unlock the Torah

Shavuot: The Torah is Your Lover

The Problem with Certainty

RSS Feed

RSS Feed