When I was a child, the prayerbook used in the Reform Movement called it "The Adoration," and the prayer expressed how we "adore the everliving God and render praise unto God." It was only with the adoption of a new Reform prayerbook in the 1970s that the original form of the traditional prayer began to emerge. The Aleinu is not just a prayer about adoring God; it is a prayer of submitting oneself to God in recognition of God's complete sovereignty over our lives and all creation.

The opening word, "aleinu," says it all. The word literally means "on us," but just as the English preposition "on" can mean obligation or responsibility (as in, "the onus is on you"), the Hebrew also denotes a requirement. We start the prayer by saying, "It is our obligation to praise the Master of all, to declare the greatness of the Shaper of all creation."

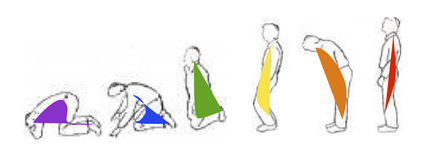

Another curious thing about the Aleinu is the prayer's climactic moment. We declare: va'anachnu korim, umishtachavim, umodim lifnei melech mal'chei hamlachim, HaKadosh Baruch Hu. The phrase, literally translated, means: "We bow, and prostrate, and give thanks before the King of kings of kings, the Holy One, blessed is He." There is a tradition of bowing on these words, but you don't usually see people prostrating all the way to the floor when they recite the Aleinu.

Originally, however, that is exactly what happened.

The Aleinu was not written to be an anthem at the end of the service. It was composed for one very significant moment in the Jewish annual holiday cycle — at the beginning of the shofar service on Rosh Hashanah.

The most important soundings of the shofar are during Musaf (the additional service) on Rosh Hashanah. Those soundings are delivered during three blessings: Malchuyot (Kingship), Zichronot (Remembrances), and Shofarot (Ram's Horns). The Aleinu originally was the introduction to the Malchuyot blessing to declare God's kingship over all reality. When recited during a traditional service on Rosh Hashanah, the prayer leader literally follows the instructions embedded in the prayer. The prayer leader falls to knees on the words "We bow," puts hands on the floor on the word "and prostrate," and touches forehead to the ground on the word "and give thanks." It is one of the most dramatic moments in all of Jewish liturgy.

The Aleinu prayer was so popular among Jews in the Medieval era that it spread to other parts of the liturgy. It is recited again in Musaf on Yom Kippur with the full prostration. It also came to be adopted as the anthem at the end of most services, but with only a bow in place of the prostration.

I find the prostration to be a beautiful practice. When I lead services for the High Holy Days, I invite members of the congregation to find a place in the sanctuary where they will have a small piece of floor in front of them so they can prostrate along with me to the prayer. Even when only a few people do the prostration, it signals a moment of tremendous power for the whole community.

Think of it this way. Yom Kippur is the day when we make ourselves completely vulnerable before God and (more importantly) before ourselves. This is the day when we own up to all the things about ourselves that are difficult to admit. It is not only hard to admit our sins and mistakes; it is also hard to face the very nature of our existence.

On Yom Kippur, we look into the abyss and admit that our lives are temporary, fleeting, and largely futile. There is no better day of the year to lay yourself flat on the floor and give up all your pretenses and conceits. This is our day to be spiritually naked and admit that the things we usually think are so important — our accomplishments, prestige, learning and wisdom — are just a facade we use to convince ourselves that we are something big and important. The truth that Yom Kippur comes to teach us is that we only matter to the extent that we live our lives in service to something greater than ourselves. We have an obligation to do that. Everything else is window dressing.

In just a few hours, Yom Kippur will begin again. The day is long and it grinds us down. It is meant to. This is our day to accept upon ourselves the obligation to see ourselves as we really are, to lay down our egos, fall flat on the ground, and awaken to the highest within ourselves.

G'mar chatimah tovah.

May you be sealed for a good year.

Other Posts on This Topic:

Steve Jobs and Yom Kippur

Bo: Hitting Rock Bottom

RSS Feed

RSS Feed