On the morning of September 11, 2001, like millions of other people, I first heard the news of two airplanes flying into the towers of the World Trade Center in New York. My wife and I huddled around the television set, with our not-quite-three-year-old child. We stayed there for much of the rest of the day, watching the horrifying images, worrying about the people we knew in New York City. Were they okay? How had they been affected?

As I look around this room, I know that everyone here remembers that day and knows exactly where they were when those towers fell down. Where were you that day? What did you do, and how did you feel on that day?

Just before noon on January 28, 1986, I was rehearsing a play in the Theater Arts building at Oberlin College. I heard from a friend that there had been an accident. I watched on a small television in the department office to see images of the Space Shuttle Challenger exploding just a minute after launch. I tried to imagine the experience of the astronauts trapped in the explosion. When that became too painful, I stopped and just cried.

As I look around this room, I know that most of the people here remember that day and knows where they were when the Challenger exploded. Where were you? What did you do, and how did you feel?

On the morning of November 22, 1963, my mother and grandmother took me with them on a trip to a dress shop in Manhattan. While they were in a changing room, my mother heard commotion outside and knew something was wrong. She heard a woman say that the President had been shot. Immediately, my mother, grandmother and I went back to the apartment and spent the next three days watching the news, sobbing along with the rest of the country.

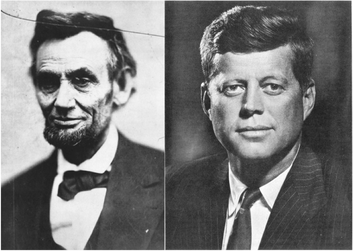

I have no memory of that day, exactly fifty years ago today. As I look around this room, though, I know that many of you do remember that day and know where you were when President Kennedy was shot. Where were you? What did you do, and how did you feel?

Each of these moments from the past half century was a moment of trauma — for our country and for the individuals who experienced them. Our world was turned upside down and shattered. At some level, a feeling of security that we had grown used to was taken away from us — the safety of our nation from attack within its borders, the pride we felt in our nation’s space program and our ability to reach out into space, the reassuring smile of a handsome young president whose smile sang of Camelot. All of that can be taken away in an instant leaving us feeling bereft, disoriented, and pained to imagine how the world will ever feel the same again.

Such moments can destroy us. They can make us sink into despair and withdrawal. However, they also can be moments of transformation that allow us to become better than we thought we could be.

Just after 9/11, it seemed like we would never be the same again. Some people felt that, if there are people in the world who hate us so much, we should not waste our time engaging them in any way. We should just let our bombs blow them out of existence. Some people said that. Some still do. But, as a society, we have decided that we can do better. The painful lesson of 9/11 has been that we must not put our heads in the sand and use our military strength as a substitute for thoughtful and open-eyed engagement. We must seek ways to create peace, not just war.

There was a moment after the Challenger disaster in which we did slip into despair. We grounded our space program for 32 months of investigation, recrimination and sorrow. Some said that the price for exploring space was just too high, both in dollars and in lives. Some said we should stick to more practical and earthbound pursuits. Some still do. But, as a nation, we have decided that we can do better. This past Monday, I stood in my driveway to watch the Maven spacecraft launch from the John F. Kennedy Space Center to explore the martian atmosphere. NASA now projects that manned flights to the International Space Station from U.S. soil will begin again in 2017. We have not stopped dreaming of the stars.

The Kennedy assassination was, in some ways the most traumatic experience of all during my lifetime. Adlai Stevenson said presciently at the time that, “All of us..... will bear the grief of his death until the day of ours.”

The Kennedy assassination, too, might have been a moment in which America could have given up on its dreams. President Kennedy had stirred the country to hopes of Camelot and a better society. After his murder, it would have been easy to allow the spirit that Kennedy represented to be crushed.

In some ways, it was. After the assassination, we became a bit embarrassed by the naivety of our talk of building a “great society.” Our politics became more crude and cynical. We began talking about foreign and domestic policies that were “realistic” and that “satisfied our narrow interests,” instead of talking about our ideals and reaching for our highest aspirations. A decade after Kennedy’s death, we thought we had hit the bottom when Watergate taught us just how low the politics of cynicism could take us.

However, another part of the truth of the past half century is that we have made some of our greatest progress through our determination not to let Kennedy’s murder also become the death of the dream he embodied. Lyndon Johnson got Congress to pass the Civil Rights Act, largely as a tribute to President Kennedy. We did put a man on the moon in 1969, just as President Kennedy told us we should. President Reagan’s declaration, “Mr. Gorbochov, tear down this wall,” contains an unmistakable echo of Kennedy’s call, “Ich bin ein Berliner.” And the very idea of electing the first African-American president has its roots in Kennedy’s determination to end legal barriers faced by Black Americans, once and for all.

When painful, disorienting, gut-wrenching tragedies come into the life of our nation, or into our own personal lives, there is always the temptation to withdraw and despair. Inevitably, tragic losses do affect us and they do scar us in ways that are difficult to understand until long after the fact. But they are also a moment to reassess ourselves and to rededicate ourselves to the things we believe in.

This week marks another American anniversary. One hundred and fifty years ago this week, Abraham Lincoln stood at Gettysburg and gave one of the most memorable speeches in U.S. history. He said, “It is for us the living … to be dedicated here to the unfinished work…” Lincoln spoke, “From these honored dead we take increased devotion to that cause for which they gave the last full measure of devotion — that we here highly resolve that these dead shall not have died in vain — that this nation, under God, shall have a new birth of freedom — and that government of the people, by the people, for the people, shall not perish from the earth.”

Lincoln speech came at another moment of trauma, standing upon land that was still blood-stained from a horrifying battle. He used the occasion as a moment — not of despair — but of transformation.

He said that this nation was “conceived in Liberty, and dedicated to the proposition that all men are created equal.” Was that actually true in 1776? Historians are doubtful. Few of the signers of the Declaration of Independence had any thought that the United States would be a nation that regarded equality as one of its founding principles. All of them were men. Most of them were aristocrats. Many of them were slave owners. Yet, 87 years after the founding of this nation, Lincoln created a new American identity built on the ideal of equality for all.

Tragedy and trauma scar us. They can make us doubt ourselves. They can make us wonder whether our dreams were too lofty or too unrealistic. Sometimes — as we have seen in recent history — they make us scale back our expectations. But the higher call, as Lincoln wrote 150 years ago, is to allow tragedy to become the foil against which we resolve to transform ourselves for the better.

That is also the story of Joseph in this week’s Torah portion. Joseph, the favorite son who was thrown into the pit and sold into slavery by his own brothers never once in the story fell into despair. Even after circumstances placed him in the dungeon, he looked for ways to transform his situation up from the depths, all the way to the heights.

Today marks a dark day in the history of our country. It is one that tests our resolve and makes us wonder whether we have tried to do too much and whether our dreams have been too lofty. If you have been around long enough to remember the last fifty years, you can also be optimistic enough to hope for the best in the next fifty. If your years, like mine, fall short of remembering fifty years, let your gaze be extended even further forward.

We can overcome all kinds of sorrow in our private lives and in the life of our nation. We can be better — as individuals and as a society — than our regrets and our pain would ever allow. We can climb higher and aspire to greater achievements when we release ourselves from self-doubt and fear and allow ourselves to remain committed to the values of peace, discovery and hope.

Shabbat shalom.

Other Posts on This Topic:

The Pit, the Water, the Scorpion, and Being a Good Person

Vayigash: Finding a Way Out of the Pit

Hope after Despair

RSS Feed

RSS Feed