| It seems that our society is divided evenly between those who consider themselves religious and those who reject organized religion entirely. The non-religious often say that they do not need religion to be "a good person." The religious find it implausible that a person could remain true to a moral life without a religious foundation. It is a debate in which liberal Jews, like me, can feel divided. For myself, I do not believe that living a moral life—being "a good person"—depends on any one particular religious belief or practice. I know many good people who are able to pass good values on to their children without a commitment to a particular religion. |

Let me also say that, I think, many of the "non-religious" have an overly-simplistic view of what religion actually offers. Religions, including Judaism, are often caricatured as providing little more than children's Bible stories, quaint rituals, and a few basic moral rules that can be summed up in cliches—"Love your neighbor," "Do unto others as you would have others do unto you," and "Thou shall not murder."

There is so much more.

Torah not only teaches us to be kind, humble, grateful and giving, Torah is a path for spiritual growth throughout our lives. Life's questions only become more difficult after childhood, and childish notions of right and wrong may not help us face the challenges we encounter as adults. Torah does teach rules for doing what is right, but developing the habits of Torah also guides a person to grow throughout a lifetime. It helps us wrestle with questions about our purpose, develop appreciation for life's contradictions, deepen our devotion to our values, maintain the discipline to stay true to them, and expand in reverence for the source of our being.

Nobody learns all that as a child. It comes from living a life of questioning and searching for answers and deeper meaning. That is what Torah does. When we enter Torah—and when Torah enters us—we accept upon ourselves a set of rituals and beliefs that teach us again and again that our life has a purpose beyond merely pursuing our desires and feeding our appetites.

In this week's Torah portion (Vayeshev), Jacob's ten oldest sons indulged in their darkest desires. They despised their younger brother, Joseph, and they imagined how delightful it would be to do away with him forever. In the middle of the wilderness, where they know they will not be seen by human eyes, the brothers devised a plan to kill Joseph and throw his body into a pit (Genesis 37:20).

The oldest brother, Reuben, worried about the implications of murdering Joseph. He tried to distract his brothers from their plan so he could save the boy and bring him back home. Yet, Reuben lacked the will to tell his brothers that killing Joseph would be wrong. The unloved firstborn son did not have the courage to say what he believed. He tried to act, but it was a feeble attempt. He saved Joseph's life, but he could not return him to his father as he intended.

The story challenges us. It forces us to ask questions about the choices we have made when we have had the opportunity to speak up against something wrong. The text asks us: When do we let our darkness get the better of us? When do we settle for half measures in facing life's moral imperatives? What gives us the strength to overcome our fears and our reluctance to take necessary action? These are tough questions for a tough world.

Eventually, the brothers followed Reuben's advice and threw Joseph alive into the pit. The text says, "The pit was empty; there was no water in it" (verse 24). Perhaps it is a metaphor for the dry, loveless relationship between brothers who were consumed by jealousy and hatred, and who had no leader among them to stand up for what was right.

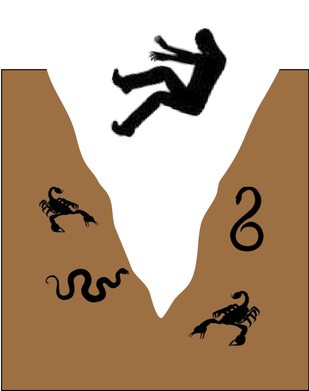

The Talmud (B. Shabbat 22a, B. Chagigah 3a) observes a redundancy in the phrase. If the pit was empty, it should be obvious that there was no water in it. Why does the Torah need to say that there was "no water in it" after saying "the pit was empty"? The rabbis conclude that the text means to say that the pit was empty only of water, but it did contain other things—snakes and scorpions.

Water, in the Jewish imagination, often is used as a symbol of Torah. Both water and Torah are sources of life in changing forms. The rabbinic interpretation of the verse becomes a lesson about our own lives: Where there is no Torah, there will be snakes and scorpions. When we don't take the time and energy to fill our lives with a tradition that teaches us, nourishes us, sustains us, and allows us to keep growing throughout our lives, we risk that our lives will be filled instead with things that threaten us and do us harm.

The contemporary Jewish thinker, Rabbi Zalman Schachter-Shalomi, puts it like this, "The mind is like tofu. By itself, it has no taste. Everything depends on the flavor of the marinade it steeps in."

If we don't feed ourselves with Torah, we will be fed by something else.

I do not claim that a person must be religious in order to be good. I do not teach that the Torah is the only path to living a life that is meaningful and fulfilling. But, if a person does not fill his or her life with a soul-broadening tradition that represents thousands of years of struggling and searching for the highest within the human spirit, what will fill that person's life? Many of the alternatives our society has to offer—television, video games, our work and leisure activities—can be as dangerous to our souls as snakes and scorpions are dangerous to our bodies.

Torah is more than a collection of children's stories. Judaism is not just a collection of antiquated rituals. Our tradition offers much more than a basic lesson in good behavior and moral development. It gives us life and a path to finding, meaning, fulfillment and joy.

Other Posts on This Topic:

Nitzavim-Vayeilech: Is There Such a Thing as a Religious Reform Jew?

Bereshit: First Crime, First Punishment

RSS Feed

RSS Feed