Twenty years ago, I was a first-year rabbinic student at Hebrew Union College in Jerusalem. That year was a momentous one for me, filled with unforgettable experiences. It was the honeymoon year for my wife, Jonquil, and me. We married in May of 1995 and flew to Israel just a month later for me to begin my rabbinic studies. It also was the first time I had ever been to Israel. I spent the year struggling to learn Hebrew, struggling to understand a culture very different from that of the United States, struggling to survive a very rigorous academic program.

That also was the year that Yitzhak Rabin was assassinated as he was leaving a peace rally in Tel Aviv. For Israelis, it was their JFK assassination. Only it was worse. It was the moment in which everything that Israelis knew about their country changed overnight. It was a moment when, for some Israelis, a dream of peace was shattered; and for other Israelis, it was a moment when a horrifying disaster was averted.

For me, a Jewish American who felt deeply connected to Israel, and yet not really a part of Israeli society, it was a moment of disorientation within disorientation. It was shattering and heartbreaking. It was a time of seeing Israelis at their best, and at their worst. It was a moment I will never forget within a year that I will never forget.

Here is what happened.

On the night of Saturday, November 4, 1995, Prime Minister Rabin was leaving a huge peace rally at Kings of Israel Square in Tel Aviv. He walked down the steps of Tel Aviv City Hall toward his car. A man named Yigal Amir slipped through the bodyguards to fire two shots into Rabin’s back with a semi-automatic pistol. Amir had painstakingly modified the weapon and the bullets over the previous two years with the single intention of killing the Prime Minister. Rabin was taken to a nearby hospital after a period of confusion. Rabin died on the operating table less than an hour later.

When Israelis learned that Rabin had been shot, most assumed that the assassin was a Palestinian Arab. The truth was much harder to accept. Yigal Amir was an orthodox Jew who, like many other Israelis who identified with the political and religious right, stood in angry opposition to the peace process that Rabin had championed. The Israeli right was angry about the signing of the Oslo Accords, which would place large parts of Judea and Samaria (the West Bank) under the control of the Palestinians. There was even talk of a peace deal that would return the Golan Heights to Syria. The country was divided and the rhetoric had been getting ugly.

In the weeks before Rabin’s assassination, there had been posters and billboards around the country (I remember seeing them) that pictured Rabin in the black and white keffiyeh headdress worn by Yassir Arafat and other Palestinian nationalists. There was a poster plastered around the country showing Rabin dressed in a Nazi officer’s uniform.

Yigal Amir was seized and arrested immediately after shooting Rabin. Eventually, he was put on trial, convicted, and sentenced to life imprisonment. In the days after the assassination, there were numerous news reports that Amir had received approval for his assassination attempt beforehand from right-wing rabbis who declared that it a case of “din rodef,” the law that permits one to kill a pursuer in order to prevent him from killing first. To this day, there are many right-wing Israelis – almost 50 percent – who believe conspiracy theories that say that Amir was not Rabin’s true killer.

I had gone to bed early with a headache that Saturday night. Jonquil stayed up to read. A few hours later, she came into our bedroom to wake me up because she had noticed that all of the Israeli television stations had gone off the air. She was concerned because they all had the same Hebrew message on a black screen. She couldn’t read Hebrew, but she sensed that something was very wrong. I got up, looked at the screen, and told her what it said. “Broadcasting is suspended in respect to Prime Minister Yitzhak Rabin, may his memory be a blessing.”

We were stunned. We didn’t understand how Rabin, the virile former army commander could be dead. We turned on our short-wave radio and listened to the BBC World Service tell us that Rabin had been assassinated. We cried.

The next day, hundreds of thousands of people gathered in Kings of Israel Square in Tel Aviv to mourn Rabin’s death. They lit candles. They sang songs. In Jerusalem, more than a million people lined up to view his casket in front of the Knesset to pay their last respects. Jonquil and I were among them. We walked along the route to the viewing area with some of my classmates from HUC. I have never heard so much silence from so many people. The line just shuffled along with nothing more than quiet murmurs for hours. We later heard one news report that said that one in six of all of the adults in the entire country had viewed the casket that day.

On Monday, November 6, 1995, twenty years ago today, Rabin was buried on Mount Herzl. The funeral was attended by many world leaders, including President Bill Clinton. He closed his eulogy with the words, “Shalom, chaver” “Goodbye, friend.” I watched on television in my apartment along with a few of my classmates, including Helen Abrams’ grandson, Michael Schwartz. I remember that Michael and I stood up in front of the television when we heard them reciting the Kaddish.

Israelis love bumper stickers. In the days that followed the funeral, many of the political bumper stickers in Jerusalem – left and right – were replaced with new stickers that said, "Shalom chaver," "Goodbye friend."

I wrote an email (which was still a novelty in those days) to all of my family and friends back in the United States on the day after the funeral. I told them about what my professors had to say in the days following the assassination. This is what I wrote:

“My teachers – all of whom have lived in Israel for many years, and some of whom are native – spoke to us of their feeling that ‘the writing was on the wall’ for such a thing to happen. Israeli society has become increasingly fractured in recent years. The level of violence among Jews has grown. Lines of 'normal' communication between supporters and opponents of the peace process have been almost completely cut off by anger and by the nearly total division between Israel’s ‘religious’ and ‘secular’ societies.

“One of my professors said she was devastated by a threefold tragedy: that this happened in the Land of Israel, that it was perpetrated by a Jew, and, most grievously, that it was done in the name of Judaism. Judaism is the religion that is so sensitive to the spilling of blood, she said, that we cannot even kill an animal for food without acknowledging God’s sovereignty over all life. Judaism is the religion whose creation is bound in the moment that Avraham’s knife was stopped from taking the life of another Yitzhak. How has Judaism been torn to shreds, that it could be twisted to justify this?”

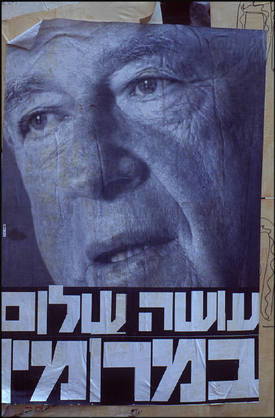

I pondered in my email back to the States, “What will happen now in Israel? Today there sprung up all over Jerusalem a new poster with Rabin’s face. Under the photo are familiar words from the Kaddish, ‘Oseh shalom bimromav.’ In the context of the prayer, the words mean, ‘May the one who makes peace in heaven,’ but in this context they could be translated as, ‘The one who makes peace is in God’s heaven.’ Maybe Rabin’s death will draw together the people of Israel to find a way to reach reconciliation. If so, we will continue the prayer to say, ‘he will make peace over us all and for all Israel.’”

Twenty years later, I look back on the moment of Rabin’s assassination not as a moment of rebirth and renewal, not a moment that unified the Jewish people, but as a harbinger of two decades of deeper divisions, heightened partisanship and polarization, and waning interest in keeping the Jewish people together. I cannot tell you had sad that makes me feel.

Today, Kings of Israel Square in Tel Aviv has been renamed Yitzhak Rabin Square. Yet, Israel’s current Prime Minister has done little to keep alive the dream of peace that Rabin tried to make real. Walking by the square in the streets of Tel Aviv, there are many school children who have to ask their parents, “Who was Yitzhak Rabin?”

I will admit that I am not nearly as optimistic about the future today as I was twenty years ago. I am sure that my change in spirit has a lot to do with the difference between being 32 and being 52. Twenty years ago, I was ready to see signs everywhere that the tide was turning, that the instinct toward peace would inevitably win out over the instinct toward fear and separation.

Now, I am not so sure. But that turn from optimism toward the direction of pessimism has only redoubled my resolve that we must do whatever we can to help peace win. I no longer believe that peace is inevitable. It will only happen if we force it into existence. We must work with all our might to make it real.

Shabbat shalom.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed