| Insurance companies and public health administrators must make cold calculations about the value of human life. They decide how much is too much to spend on a medicine, a procedure, a piece of medical equipment. According to one standard, a procedure must extend the life of at least one person for every $50,000 spent. If providing the procedure to a thousand people would result in an added year of "quality of life" for one of them, it makes sense to spend an average of $50 on the procedure for each patient. If it extends life for ten people, you can spend up to $500 per person. But if the procedure costs more…well, that's too bad for those who would have benefited. |

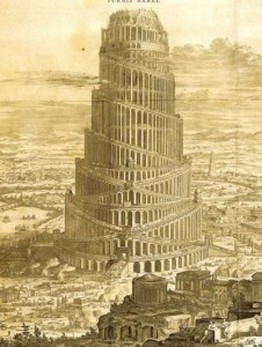

In this week's Torah portion, Noach, we read the story of the building of the Tower of Babel. After the Flood, the people decided to build a tower out of bricks that would extend up to heaven. God, seeing the people build the tower, frustrated their plans by confusing their speech, causing each person to speak a different language. Unable to understand each other, the people abandoned the tower and scattered (Genesis 11:1-9).

The ancient rabbis asked an inevitable question about the story: What was wrong with building a tower to the sky? Isn't it good for people to aspire toward heaven? The rabbis read between the lines of the story to show how the problem with the Tower of Babel was that it made people devalue human life.

According to a classical midrash, the Tower was of such great height that it took a person a year to climb from the base up to the top. Every brick that was baked on the ground and brought to the top of the Tower was, therefore, considered extremely valuable—it represented a huge investment in energy and time. As the Tower grew taller, according to the midrash, its builders began to see bricks as more precious than people. "If a person fell and died they paid no attention, but if a brick fell they sat and wept, saying, 'Woe upon us! Where will we get another to replace it?'" (Pirke De Rabbi Eliezer 24:7).

The sin of the builders of the Tower of Babel was not that they wanted to climb up to heaven. They may have begun their project with good intentions, but, in doing so, they turned human beings into mere commodities of limited value. That was their sin. They lost touch with the truth that human life is invaluable, that we are each created in the image of God.

Our society today wants to do great things, too. We want to build great cities. We want to explore the universe. We want to build devices that give us amazing powers of calculation, communication and creativity. We want to amass wealth, luxuries and military security. But at what price? What objects of our own devising do we value more than the lives of human beings?

In the realm of medicine, health insurance and public health policy, we legitimately weigh how we spend money to save lives. We want to make wise choices to maximize our resources to do the most good. Using a formula based on costs and benefits is how we say that in numbers. But, even there, we recognize the dangers of putting a price tag on life. Human beings are not numbers.

How much more, though, do we need to be careful when our appetites for power, prestige, comfort and security blind us to the value of human life? Which bricks do we mourn as the bodies fall from today's towers? We must avoid the error of Babel by not ignoring the price we pay when the pleasures we seek lead to the exploitation of works, the poisoning of our environment, and the death of innocents.

Each life is of infinite value, including our own. When we ignore the value of the lives of others, we cheapen our own life, and we degrade our relationship with the one in whose image we are formed.

Other Posts on This Topic:

The Problem with Certainty

Balak: Seeing God's Image in Our Enemies

Letting Go

RSS Feed

RSS Feed