If you have ever been a parent—and, perhaps, if you have ever been the child of a parent—you know about the frustrating experience of reacting to children’s misbehavior. As parents, we love our children even when they do not behave the way we want. But knowing how to love a child when he or she misbehaves is one of the greatest challenges we experience as parents.

Of course, we get angry. Of course, we are tempted to yell at them and to tell them how disappointed we are in their behavior. We also know, though, that the instinct to yell and chastise should be considered carefully. We do not want to become so angry that the only thing the child hears is a message that says, “You are bad.” We want to make sure that we get across a message that explains what we find unacceptable about the child’s behavior, not about the child’s person. We want to reassure our children that we love them while we also send a clear message about the consequences of bad behavior and our hopes for future improvement.

Good parents know that there is no one-size-fits-all solution to the dilema of parenting through bad behavior. There are some situations that might be best addressed with a mild reprimand—such as, “I saw that, Rachel, and I did not like it.” There are other situations that call for sterner consequences, such as the loss of a privilege, the demand for a direct apology, a “time out,” or paying back a loss suffered because of a hurtful action.

The question that parents should ask themselves before reacting to a child’s misbehavior—and I know this is difficult—is this: For whose sake am punishing this child? Is the consequence I am decreeing for the sake of the child’s benefit? Am I doing it because of some personal need for myself? Or, is it for the sake of some other person? When we are clear with ourselves, as parents, about who benefits from our response to bad behavior, we are more likely to make good choices that help direct the child to better behavior in the future.

This week’s Torah portion, Ki Tisa, tells us a story about misbehavior, about punishing bad behavior, and about the motivation behind the punishment. The story is one that you know. It is the story of how the Israelites built a Golden Calf, an idol to worship, even while Moses was on top of Mount Sinai receiving the tablets of the Ten Commandments directly from God.

According to the Torah, at the end of forty days on the mountain, God told Moses what the Israelites had done. God decreed that the Israelites would be destroyed for their sin and that God would form a new covenant with Moses’ descendants. Moses had to argue with God not to destroy the Israelites, and, instead, to have compassion on them. Once God’s anger relented, Moses went down the mountain with the tablets. When he reached the Israelites at the base of Mount Sinai, he heard their singing and saw their dancing as they worshipped the Golden Calf. The Torah tells us:

“As soon as Moses came near the camp and saw the Calf and the dancing, he became enraged. He sent the tablets from his hands and shattered them at the foot of the mountain” (Exodus 32:19).

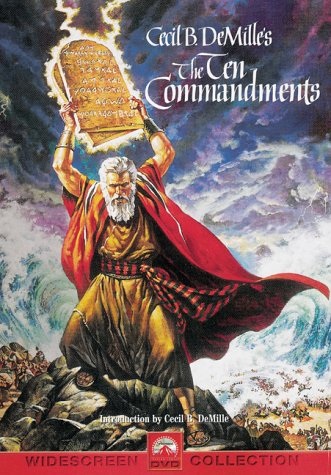

Now, you may think that you know why Moses smashed those tablets written by the hand of God. You’ve seen the movie and you remember the anger that was on Charlton Heston’s face when he lifted the tablets over his head and brought them down. It is a moment that might remind you of how angry you felt when you saw your child doing something wrong. It might remind you of how you felt when you saw your mother or father become enraged with your behavior. In our imagination, Moses smashed the tablets in anger.

However, there is far from a consensus among Judaism’s classical commentators about this. The smashing of the tablets was certainly a consequence of the Israelites’ bad behavior, but it is not clear what feelings or motivations in Moses brought it about. Understanding that moment can be a way for us to understand our own choices as parents when a child does something that makes our blood boil.

Deuteronomy Raba, a collection of midrashim from the 1st or 2nd century, agrees with Cecil B. DeMille that the main emotion going through Moses’ mind was sheer rage. However, the midrash wonders why Moses became so angry only after he came down the mountain. God already had told Moses about the Golden Calf when he was on top of Mount Sinai. Why did he not react with anger then? The midrash even has God asking Moses why he did not get angry until he saw the idol with his own eyes. God says, “Moses, did you not believe Me (when I told you) that they built themselves a calf?”

This midrash wants us to know that it was the sight of the Golden Calf that triggered Moses’ anger. Moses’ fury was not calculated or premeditated. It was a fiery, impulsive reaction. So much so, the Torah says, that he shattered the tablets that had been written with God’s own hand.

If we follow this midrash, we could compare Moses’ anger with that of a parent who punishes a child impulsively—a gut reaction to seeing something that is not right. You might say that Moses is like a parent whose response to misbehavior is for the sake of appeasing his or her own anger.

As I said, this is not the only interpretation that our tradition offers for Moses smashing the tablets. Rashbam—a twelfth century commentator who lived in France—sees it differently. Rashbam says that Moses acted more out of despair than anger. Remember that, at this point, Moses was eighty years old and he had just carried two heavy tablets all the way from the top of Mount Sinai down to the foot of the mountain. Rashbam asks, What gave him the strength to do that? It must have been some supernatural power that came to Moses from God and from the words of Torah that were inscribed upon the tablets.

Rashbam argues that, when Moses saw the Golden Calf, that power disappeared. In the face of the Israelites reveling in their idolatry, Moses’ strength weakened, or the tablets themselves grew heavier. When the Torah says that Moses “sent them from his hands,” Rashbam believes that it is because Moses no longer had the strength to hold them. Moses cast the tablets a little way from himself so that they would not injure him as they fell.

According to Rashbam, Moses broke the tablets for the sake of protecting himself. He did it in order to save himself from the inevitable danger posed by the Israelite’s idolatry.

For many parents, this is a familiar story. When we see our children misbehaving it can feel like we have been sapped of our strength. We act out of despair. We feel a great weight on our shoulders and we are not sure if we are even capable of raising children. Sometimes, when we react to our children’s bad behavior, we do so in a self-protective way. We order them to go to their room—and, if we are honest, sometimes it’s just to get them out of our sight. We might yell at the children some, but it is only to keep ourselves from crying in front of them. This is another example of parents responding to children’s misbehavior for the sake of their own needs, not their children’s needs.

There is also a third possibility, and this comes from the 15th century Italian commentator, S’forno. He says that Moses neither broke the tablets for the sake of appeasing his anger, nor for the sake of protecting himself in a moment of weakness. S’forno says that Moses did it for the sake of the Israelites.

According to his interpretation, when Moses saw that the Israelites were actually happy about the terrible sin they had committed, he knew that something dramatic needed to happen to change the way that they thought about themselves. Breaking the tablets, says Sforno, was a dramatic gesture intended to force the Israelites to reconsider their values and their choices.

Imagine, again, a parent who discovers a child misbehaving. Often, the child shows immediate remorse once he or she recognizes a parent’s disapproval and stop misbehaving. Sometimes, though, the child will have no awareness that he or she has done anything wrong and becomes defiant, even after being discovered, because the child feels no shame about what he or she has done.

S’forno says that this is the situation in which Moses found himself. Moses was genuinely angry, for sure, but he also was concerned about how unaware the Israelites were about their own deplorable behavior. S’forno says that Moses’ display of anger was calculated to get the Israelites to understand the nature of what they had done. He hoped to awaken them to a moral awareness, without which, the tablets and the Torah would be meaningless to them.

Moses, says S’forno, broke the tablets for Israel’s sake. He hoped to make the people worthy of the tablets by awakening them to the need for a moral structure.

This is like the response of parents who feel true anger but who do not let their anger dictate their response. Instead, they think about the message that will prompt their children to reconsider their actions. Their goal is to change their children’s behavior—not by coercion—but by awakening them to the seriousness of the choices they have made, by getting them to think about what they have done, and by encouraging them to make better choices in the future on their own.

When we see other people behave badly—whether it is a child, an adult, a spouse, a friend, a stranger, or a public figure—we can get angry. Before we act on that anger, though, we should ask ourselves: For whose sake is my display of anger? Does it do any good? Are there times when displaying anger is not appropriate? Are there ways of showing anger that are more effective? How can I use my anger to do the most good against things that are wrong?

Of course, when the person who angers us is a child—especially when it is our own child—the stakes are even higher. Instinctively, we want to do what is right for our children, but sometimes it is difficult to know what that is. By asking ourselves these questions, by focussing on actions that serve the needs of our children first, we can make wiser choices and raise children who are ready to receive Torah, a teaching about how to live a good life.

Shabbat shalom.

Other Posts on This Topic:

Vayetze: Righteous Anger

Ki Tisa: The Golden Calf Is Within Us

RSS Feed

RSS Feed