| How do we make sense of a world in which good people suffer while evil flourishes? How do we reconcile belief in a benevolent and powerful God with a world in which the rewards for doing good are hard to see? This Sunday will mark the tenth anniversary of one of the most despicable and evil acts of the 21st century. Nearly 3,000 innocent people were murdered on September 11, 2001, by people who claimed to be acting in God's name. How do we understand that? How can God tolerate it? |

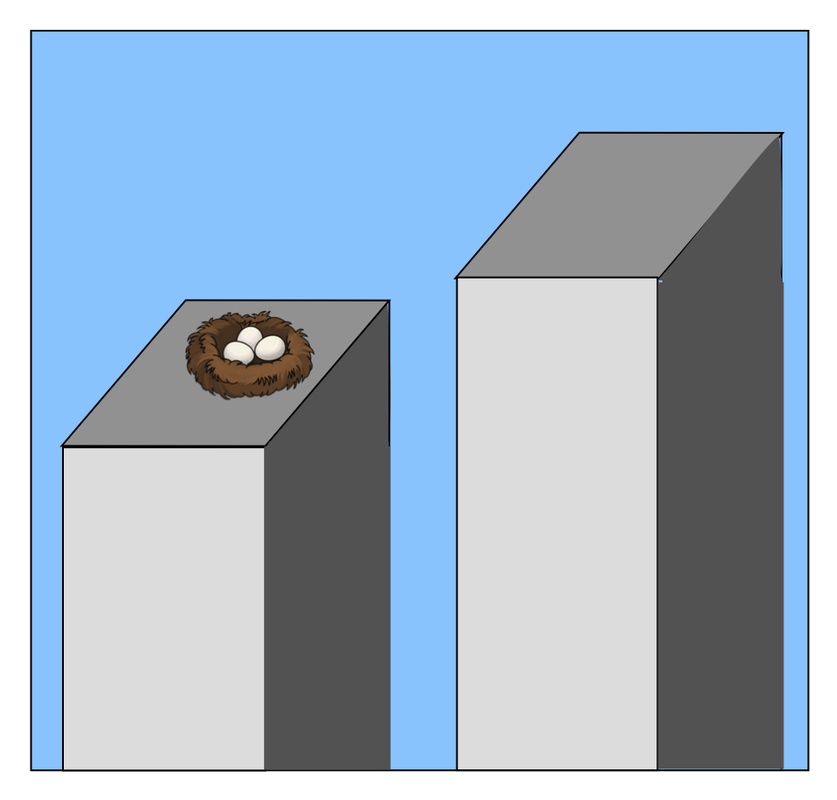

If you should come upon a bird’s nest while traveling, in a tree or on the ground, and there are chicks or eggs with the mother bird sitting on the chicks or eggs, you shall not take the mother from the children. You certainly must send away the mother and take for yourself only the children, so that it will go well for you and you will lengthen your days. (Deuteronomy 22:6-7)

It really is a lovely mitzvah. While we require food to live, we must do so in a way that is considerate of all life, even the life of a bird. We must not take the mother along with her children.

It is the second part of the mitzvah that was challenging to the rabbis—the part in which the Torah promises, as a reward, that "it will go well for you and you will lengthen your days." The rabbis, who knew about life's tragedies and unfairness, ask the question: Is it really so?

They raise a hypothetical question (B. Chullin 142a): "Suppose a father says to his son, 'Climb up that tower and fetch me some chicks.' The boy climbs up, sends away the mother bird, takes the children, but on the way down he falls and dies. Where is the 'lengthening of his days'? Where is the 'going well' for him?"

And then, just to raise the stakes, the rabbis claim that this really did happen once. The Talmud states: "Rabbi Jacob saw it happen."

What then? Does God not care? Do those who observe God's laws, who respect life and act decently, have nothing better to hope for than broken promises?

The rabbis answer this profound question enigmatically. They say, "There is no mitzvah in the Torah with a stated reward that is not connected with the resurrection of the dead." All the promises of good rewards for acts of goodness are fulfilled, but not in this world, the rabbis tell us. It all must be understood as being part of the world beyond this.

The rabbis go on to explain that, rather than expecting a reward in this world, we should understand that “lengthen your days” refers to a world in which everything reaches its ideal length, and “it will go well for you” refers to a world in which everything is well.

Now, before you reject this as a theological cop-out—an empty promise of "pie in the sky when you die"—let us consider what the rabbis are really saying here. They are admitting that there is no promise of material reward for the righteous. The righteous suffer and know pain just the same as everyone else. The Talmud says flatly, "There is no reward in this world for a mitzvah." That's a gutsy statement for people who believe profoundly in a just and good God.

What the rabbis do promise is hard to pin down. They promise "olam ha-ba," usually translated as "the world to come," but with deeper resonance than we usually think. The word "olam" in Hebrew does mean "world" or "universe," but it also means more. "Olam" is also the "forever" in "l'olam va'ed," meaning "forever and ever." The word "olam" means both "all of space" and also "all of time." It is the ancient Hebrew equivalent of "the space-time continuum." In short, it is another word for "reality."

Taken this way, we can understand the promise of a reward in "olam ha-ba" as a reward in "another reality." But what reality is that? It is the reality of our hopes and dreams. It is the reality we experience when we know that real happiness does not depend on physical comfort and material plenty.

Our good actions receive reward in the reality we experience when we feel ourselves to be part of something beyond ourselves. It is not in a time far away in the future or up in heaven, rather, it is the reality we can experience any time we wish by entering into awareness of the divine in each moment.

The section of the Talmud that discusses the bird's nest ends with the introduction of another character. It says that Elisha ben Avuyah, the great rabbi who left Judaism and gave up the ways of the Torah, may have committed his apostasy after seeing "this very thing"—a boy falling to his death after sending away the mother bird. We can imagine Elisha, who knew the reward associated with this mitzvah, deciding when he saw this horror that the Torah was all lies and broken promises.

And the Talmud adds that, according to others, Elisha ben Avuyah left Judaism when he saw how the Romans murdered the sages of his generation and left their bodies to rot on dung heaps.

Can we blame him? Don't we also feel tempted to dismiss God and the Torah as a bunch of fairy tales when we remember images of innocent men and women leaping to their deaths from the World Trade Center? Where is God and where is God's promised reward?

The answer can only be that there is no reward in the reality that only knows material pleasure and physical comfort. There is no balm for the righteous to be found there. Our truest and deepest joy in life is to be found in another reality. The reward for our soul is in the reality where we know ourselves to be part of God.

If you know people who have really known profound suffering, and yet experience joy, then you know that this reality is real. Olam ha-ba is the place where pain and deprivation do not matter because we are in tune with the miracle of just being alive in a world that was given to us without our asking. That is our reward. That is the source of all true joy.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed