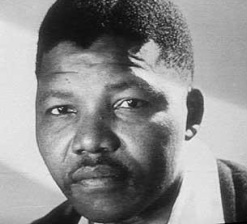

I've often said that, despite what it says on my diploma, my real major in college was "pissing off the administration." Mostly, that was over the issue of the college's investments in companies that did business in South Africa. That was the "old South Africa," a nation built on the racist system called apartheid. It was a nation that was peacefully overthrown by a movement that was led by Nelson Mandela.

As a college student, I helped organize sit-ins, marches, and educational forums to let people know about our college's role in supporting apartheid. "Free Nelson Mandela" was one of our marching cries.

As a student representative on the college's General Faculty, I helped draft a resolution calling for divestment from South Africa. With the help and support of many students and faculty members, that resolution passed in 1985. For me, a 21-year old kid at the time, it was the first time I really experienced how, when people work together, they can make a real difference to build a better society.

There are certainly those who will say today that the South Africa that Nelson Mandela helped to build is a far cry from being "a better society." South Africa today is plagued by violence, poverty, disease, government corruption, continuing racism, and an unacceptable chasm separating the "haves" from the "have-nots." But Nelson Mandela deserves to be remembered as one of the great leaders of the 20th century despite his country's many problems.

To me, as an impressionable young man, Mandela was a moral exemplar of the highest order. He was born into a family that enjoyed prosperity and privileges that far exceeded those of most black South Africans, yet he put all of those comforts on the line to wage battle against the injustice of his society. He was accused of treason in a trial that lasted from 1956 to 1961 for his non-violent opposition to apartheid. A year after he was acquitted in that trial, he was arrested again and convicted for conspiring to overthrow the government. He spent the next 27 years in prison for speaking the truth and for trying to end a hateful and racist regime.

Mandela was freed from his life sentence in 1990, mostly in response to an international campaign calling for his release. The student-led campaign on U.S. college campuses was cited frequently in the press as a major factor. Mandela then negotiated an agreement with South African President F.W. de Klerk to end apartheid and to set up free, democratic, multi-racial elections.

Despite the predictions of many in the government and the press, the new South Africa did not become a state that sought to punish the white minority that had oppressed the black majority for decades. Mandela became a champion of reconciliation and national unity. After serving one term as South Africa's first black President, he declined to run for re-election and, instead, became an international leader for peace and against HIV/AIDS.

I only saw him once in person. That was during a tour through the United States in 1994. I heard him speak on the Boston esplanade along with hundreds of thousands of others.

Mandela, to me, is one of the few figures I have seen in my lifetime who comes close to the example of the prophets of the Hebrew Bible. Like Jeremiah who called his nation to bear witness against its own sins, Mandela forced South African society to face its moral failings, to take up the obligation to feed the poor, house the homeless, and to lift the shackles from the oppressed. Like Isaiah, he promised that when his country changed its ways, it would be rewarded with a new day of rebirth and renewal. To the best of his human abilities, he worked tirelessly to fulfill that promise.

And let me draw one more connection between the life of Nelson Mandela and our tradition. In 1964, when Mandela stood trial for attempting to overthrow the South African government, he gave the speech that turned him into an icon for the cause of freedom. In that speech he spoke truths that most white South Africans were not ready to hear about their country. He spoke about how white South Africans feared democracy because it would bring an end to their monopoly on power. He told them, not unkindly, that they had a chance to redeem themselves by living up to they values they said they cherished.

He said at the Rivonia Trial:

This is the struggle of the African people, inspired by their own suffering and experience. It is a struggle for the right to live. I have cherished the ideal of a democratic and free society, in which all persons live together in harmony and with equal opportunity. It is an ideal which I hope to live for and achieve. But, if needs be, my Lord, it is an ideal for which I am prepared to die.

It was a speech that was eerily reminiscent of a speech in this week's Torah portion (Vayigash). Standing before the powerful vizier of Epypt, Judah spoke about the suffering of his father and his willingness to give up his own life to restore freedom to his brother, Benjamin. The vizier — who, of course, was really his brother, Joseph, in disguise — was so moved that he broke down in tears, relented from his anger, and freed Benjamin (Genesis 44:18 - 45:8).

This is how Nelson Mandela won freedom for his people. He spoke the truth. He told white South Africa about its own fears and its own path to redemption. In the end, apartheid itself was unmasked and the reconciliation of brothers that followed included the brother who had once been the oppressor. May it be so wherever people are oppressed.

It is difficult for me to imagine my life as it has been without the inspiration of Nelson Mandela, and I am but one of millions who will say the same. His loss is keenly felt, but the things he did in his life will continue to inspire generations to come.

Zichrono livrachah. May his memory be a blessing.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed