Psalm 65 begins with these words, L’cha dumiyah t’hilah Elohim b’Tzion. The verse can be translated as, ‘To You, God in Zion, silence is prayer.’ What can this mean? How can we praise God with mere silence? Here is a story that might explain.

There was once a man who was a great singer of popular songs who longed to be a cantor. Whenever he sang in the music hall or in a tavern, he was praised for the beautiful tone of his voice and for his perfect control of each note. However, whenever he tried to lead a service in the synagogue, the congregants would be unmoved. Some of them fell asleep. When he concluded the service, people would quickly gather their things to leave, so as not to have to answer his persistent questions, "Did you like it? Did I sing the prayers well today?" They didn’t want to talk to him about it because the service left them feeling cold and unfulfilled.

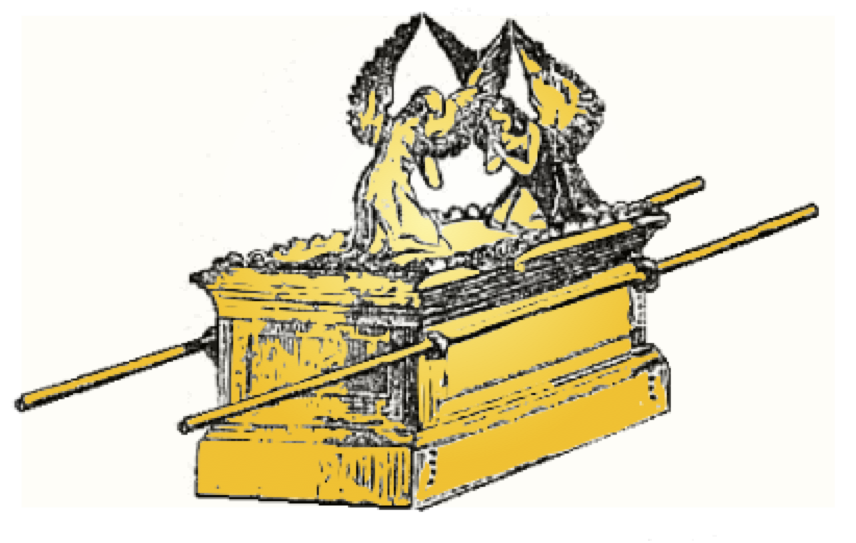

The singer was so disappointed in his inability to sing the prayer in the synagogue that he went to the Besht, the Baal Shem Tov, the great spiritual leader of the hassidim. He implored the Besht, “Please, teach me to be a cantor who will move the congregation with the sound of my voice leading the prayers.” The Besht told him, “Before you open your mouth to sing, you must hold these thoughts in your heart: You must consider that the soul of every person in the congregation is in your hands. Every note you sing will either cause their hearts to cleave to God and to commit themselves to doing God’s will, or it will cut them off from God completely. You must consider that your voice will become like the parochet, the screen that was placed in the ancient Temple in front of the Holy of Holies. It is within your power to open the screen and to bring the people into the closest possible connection to the Holy One of Blessing, or to forever be a barrier that keeps them separated from the Source of Life.”

The singer solemnly accepted the instructions of the Besht. He prepared for his next appearance in the synagogue by spending an entire week in constant thought and meditation over the teaching that the Besht had given him. He actually visualized in his mind the souls of all the congregants sitting on the notes that came out of his mouth. He imagined that his voice was the holy parochet of the Temple that guarded the doorway between this world and God’s presence.

On the day of the service he was assigned to lead, the singer walked into the synagogue with his head swimming with these thoughts. As he climbed the steps of the bimah, he imagined how his singing could bring the souls of the congregation closer to God. He opened his prayerbook and prepared to chant the opening words of the service, “Mah tovu ohalecha Ya’akov,” “How good are your tents, O Jacobs.” He opened his mouth…and nothing came out. He swallowed some water to clear his throat and tried again… nothing. Not a sound, not a note would come out him. This man, who could sing a drinking song like an angel, was utterly incapable of singing a prayer in the synagogue with meaning or spirit.

Realizing his failure, he broke down in tears on the bimah. Frantically, he turned the pages of the prayerbook, hoping that he could find one prayer that he could squeeze out of his throat. Page after page gave him nothing to sing. He could not even begin a single prayer. There was only silent sobbing heard that day from the bimah as the singer imagined his dream to be shattered, his yearning unfulfilled.

The congregation sat in astonishment as they watched the singer. None could bring him or herself to speak. They did not want to deepen the singer’s embarrassment by taking his place or by telling him to let someone else lead the prayers. For half an hour, they watched the singer turn the pages and cry softly to himself. When he finally began to come down the steps from the bimah, they gathered their things and prepared to leave, still in deep confusion.

As the singer came down the last step, he saw that the Besht was there waiting for him. The singer’s mortification grew even deeper when he saw the great man. He not only had failed himself and the congregation, he thought, he had failed the Besht. What would the Besht say? Would he tell him that he had not followed his instructions correctly? He shuddered, as his mind raced with the disgrace that would follow as soon as the Besht opened his mouth and began to rebuke him.

But the Besht said nothing. Instead, he opened his arms and wrapped them around the singer. The Besht kissed the singer on both cheeks and gazed into the singer’s eyes with a warm smile on his lips. The singer saw that there was a tear on the Besht’s face, a tear of joy.

From that day on, the man was no longer called a “singer.” He became known – not only as a chazan, a cantor – but as “The Chazan of the Besht.” Every year on Yom Kippur – at the request of the Besht – he came before the congregation for the Kol Nidre prayer, the prayer in which the congregation begins its search for forgiveness from God. On that occasion, he would stand on the bimah, open the Yom Kippur prayerbook to the first page, look out at the congregation, imagine the responsibility of helping them to return to God, and he would cry in silence.

Other Posts on This Topic:

In Praise of Silence

Meditation

RSS Feed

RSS Feed