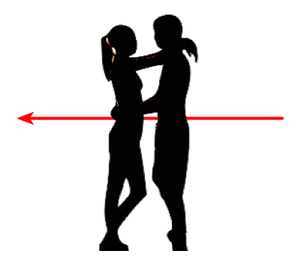

In the story, Pinchas took swift, but unauthorized, action when he saw an Israelite man named Zimri "whoring" with a Midianite woman named Cozbi. (It's a charged word, but an accurate translation of the Hebrew, לזנות, in Numbers 25:1). Pinchas picked up a spear and killed both Zimri and Cozbi. According to the text, Pinchas' zealous action averted God's wrath against the Israelites and it earned him the reward of "perpetual priesthood."

Even the ancient rabbis had a hard time understanding and explaining this story, as it implies that vigilante killing can be excused, and even rewarded, if it is done in zealous obedience to God. It's a dangerous idea. We don't want to encourage people to justify killing by saying, "God told me to do it."

The Talmud states that Pinchas was only rewarded for his murderous action because he struck the couple while they were caught in the midst of the forbidden act. Further, it says that Zimri had a right to kill Pinchas in self-defense because no court had ordered him to be executed (B. Sanhedrin 82a). By some measure, Pinchas was no better than the man he killed.

What is the Torah trying to tell us? What are the rabbis trying to say?

Zealotry is a common human experience to things that excite our anger and our sense of righteousness. When people see things they believe to be evil, they often are quick to strike (preferably with words, not spears). We can recognize this tendency in ourselves.

Think about the times when you have responded angrily to something that seemed wrong to you. Did you say something hurtful? Did you become hostile? Did you do something that you later regretted, even if you thought your anger was justified?

Jewish tradition has an ambivalent approach to such zealotry. On the one hand, it is good to be passionate in the cause of justice and righteousness. We applaud swift action to stand up for what is right. On the other hand, we are reminded that we rarely make good choices when we are enraged.

The rabbis intentionally narrowed the circumstances when actions like Pinchas' could be permitted. They warned that the line between righteous indignation and self-righteous fervor can be very unclear when we are upset. They reminded us that zealotry can backfire in terrible ways.

How should we respond when our passions are excited by things that seem wrong to us? First, we should be patient with ourselves. Take the time you need to consider an appropriate response. Consider the perspective and intentions of the other person.

Second, let your response come from your best self – your highest values and your deepest commitments – and not from anger, self-aggrandizement, or fear. Remember that we always have a choice to make things better, or to allow our anger to make them worse. Make choices that lead to healing.

Finally, be humble. None of us is perfect. Everyone makes mistakes. Remember the times when you fell short of your standards and you needed others to be forgiving toward you – not enraged. Lower your ego before you judge others.

Pinchas' story is not easy. It challenges us and may even anger us. It reminds us that there are no easy choices in this world. It reminds us to examine ourselves, our motivations, and our feelings. It tells us to do the best we can to do what is right in a world that is often wrong.

Other Posts on This Topic:

Pinchas: Zealotry

Pinchas: Phinehas' Spear

RSS Feed

RSS Feed