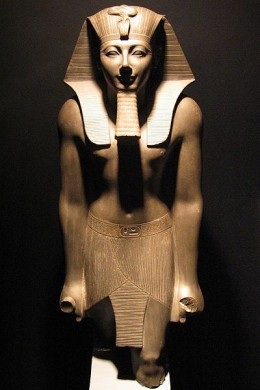

Last week's Torah portion ended with Pharaoh making a startling admission to Moses. The king of the most powerful nation on earth, who believed himself to be a god, said to Moses, "I have sinned this time. Adonai is in the right, and I and my people are the wicked ones" (Exodus 9:27). It seemed like Pharaoh finally saw the error of his ways, but Moses was not convinced. Moses responded to Pharaoh's show of seeming humility by saying, "I know that you and your courtiers do not yet fear Adonai God" (Exodus 9:30). In effect, Moses called Pharaoh's bluff and suggested: I don't believe a word of what you're saying. You still don't get it. Turns out, Moses was right to doubt Pharaoh. As soon as the plague of hail ended, Pharaoh "became stubborn and continued his sinful ways" (Exodus 9:34). |

How did Moses know? What made him so sure that Pharaoh was not yet ready to let the Israelites go? The answer may be right in the story. The Torah tells us that the plague of hail completely destroyed the flax and barley crop, but that the wheat crop was not destroyed because it ripens later in the season (Exodus 9:31). What is the importance of this? It tells us that Pharaoh had not yet given up in his heart. He still had hope of getting through the crisis without having to change his ways. He could still keep his Hebrew slaves and survive on wheat for the year.

Think of Pharaoh as being like an active alcoholic. As long as he has a pair of shoes to sell to buy the next bottle, he is not going to give up drinking. Think of Pharaoh as being like an abusive spouse. As long as he believes that his victim will come back to him, he will never stop the beatings. Pharaoh, who represents the most desperate, stubborn and incorrigible aspect of our psyches, will never let go of what he is determined to posses until he finally hits rock bottom.

Pharaoh is a part of each of us. It is the part that insists that, "The rules don't apply to me. I know that what I'm doing is wrong, but I have to do it anyway. I'm too set in my ways, so the world will just have to deal with me as I am." This is in all of us. None of us is exempt. We all have that voice within that would rather stick up for our weaknesses than do the hard work of changing and pursuing our true happiness.

It is in this week's portion that God talks back to that voice within us. God says, "How long will you refuse to humble yourself before Me?" (Exodus 10:3). It is not a demand. It is not an ultimatum. It is just a question—one that should be ringing in our ears. How long? How long will it take you to recognize that you need to change? How long until you realize the suffering you are causing to yourself and to the people who are affected by your choices? How long?

Not surprisingly, Pharaoh responded with begging and bargaining, as we would expect any addict to do. Pharaoh said, "Now, forgive my sin, just this once, and plead to Adonai your God to remove just this deadly threat from me" (Exodus 10:17). The cycle of tearful apologies, promises to do better in the future, bargaining for just one more chance, followed by more repetitions of the same bad behavior—it all seems inevitable. The only thing that will change the behavior for good, as every veteran of a twelve-step program knows, is a total breakdown of the cycle. The only thing that could have saved Pharaoh would have been the self-recognition that he was no longer in control of his compulsion and that he needed to submit his will to something beyond himself.

And, again, it is not just about Pharaoh. It is about all of us. It is part of our nature to dig in our heals to avoid the uncomfortable, ego-deflating admission that we need to change. We all have habits and behaviors that we know we would be happier without—whether it is an anxious need to keep up a break-neck speed of work, a reluctance to turn off the electronic gizmos, a repeated failure to confront the harmful behavior of others, or a stubborn refusal to see the pain we have caused. It is so hard to change, even when we know that change would make us happier.

God keeps asking the question, "How long?"

In a way, Yom Kippur serves as a way of forcing the question. A full day of fasting and pleading for forgiveness helps us to see the depths of the abyss, a foretaste of what we might experience if we allow ourselves to go all the way to rock bottom. But we don't have to wait until a once-a-year holy day to begin internalizing God's question and to start asking ourselves: How long?

Today could be the day for you. This might be the day that you say to yourself that you have run out of excuses and that you are ready, right now, to humble yourself and admit that you already have hit rock bottom.

Or, are you still clinging to the empty hope that the wheat harvest will save you from having to make yourself happy?

Other Posts on This Topic:

"Not One of Them Was Left"

RSS Feed

RSS Feed