This Sunday and Monday nights, the Lifetime Channel is airing a made-for-TV movie based on the novel The Red Tent by Anita Diamant. The book and the movie are a retelling of a very minor story in the book of Genesis that, I guarantee, you did not learn about as a child in Religious School. Either by design or coincidence, that story is also in this week's Torah portion (Vayishlach).

The story is about a character named Dinah, the only daughter of Jacob, the youngest child of Jacob’s first wife, Leah. In the Torah’s telling, Dinah has no lines, she does not speak. All that we know about her from the biblical text is that a terrible thing happened to her.

Jacob, Dinah’s father, had just arrived in the land of Canaan and had purchased land to pitch his tent and graze his sheep from the king of a nearby city. The king’s name was Hamor and he had a son named Shechem. Shechem saw Dinah and was smitten.

The Hebrew text describes what happened in a series of short phrases: “Vayikach otah, vayishkav otah, vayane’ah,” “He took her, he lay with her, and he rendered her helpless.” That last phrase, which I am translating as “rendered her helpless,” is also used a few times in the Hebrew Bible as an idiom for something sexual that men can do to women, similar to the English idiom, “had his way with her.” It might mean rape.

The text continues: “[Shechem’s] soul became attached to Dinah, the daughter of Jacob, and he loved the maiden, and he spoke to the maiden’s heart. Shechem said to Hamor his father, ‘Get that girl for me as a wife!’”

Shechem had his way with Dinah and he fell in love with her. He wanted to marry her. Did he use force to “have his way with her”? How did Dinah feel about Shechem? Did she love him, too? To our frustration, the text does not say.

Why? Why do we not know any of the important details of this story from Dinah’s point of view? Maybe it is part of the way the narrative keeps up our interest – the Bible keeps the reader guessing about what is going on in the mind of each character. Why did Shechem take advantage of Dinah? How is Hamor going to deal with his son who has put him in an awkward position? How will Jacob react when he finds out what has happened to his daughter? How does Dinah feel about the man who “speaks to her heart” and who has asked his father to arrange a marriage to her?

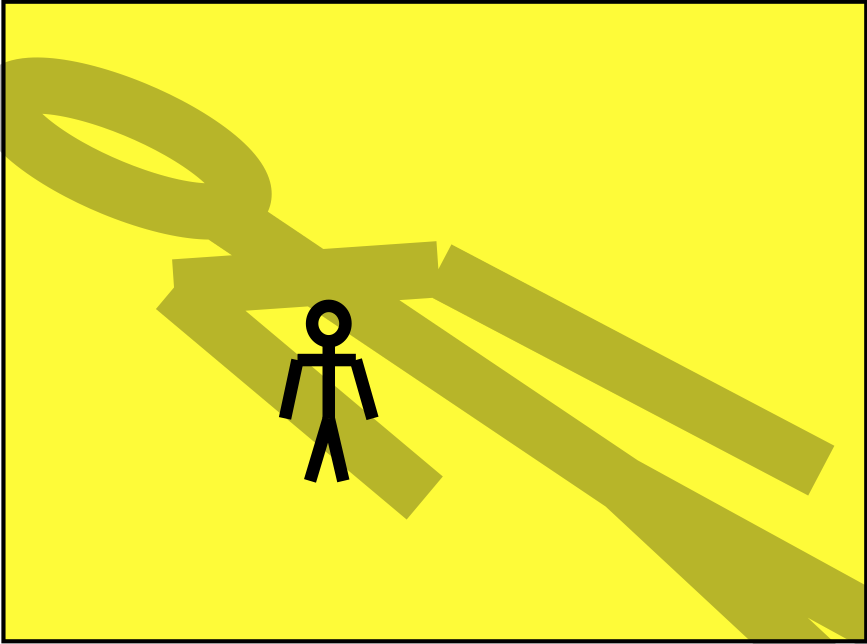

I would like to think that the Bible wants us to wonder about what is going on in Dinah’s head. I really want that to be true. However, I have a strong suspicion that it is not the case. I think the more likely reason for Dinah’s silence in this story is that her point of view just doesn’t matter to the story’s author or to the story’s original audience.

For the most part, the Bible does not care much about what women think. It especially does not care what they think when it comes to love, sex and marriage. In the Bible, when a man desires a woman, the normal thing for him to do is to arrange for marriage through the woman’s father, perhaps with the man’s father negotiating on his behalf. That is what happened when Abraham sought a wife for his son Isaac. That is what Jacob did when he wanted to marry Rachel. It seems that it is also what Shechem should have done. From the Bible’s perspective, it seems, Shechem’s biggest mistake was having sex with Dinah before those arrangements were made, man-to-man. The preferences of women had very little to do with it.

That bothers us, and it really should bother us. We don’t live in the world of this story and we do not want to. The story of Dinah is troubling to us on many levels, but all of it boils down to this – we cannot abide a world in which women have no say, in which their feelings, thoughts and desires are not only ignored, they are treated as inconsequential.

And I haven’t even gotten to the most troubling part of the story yet.

Hamor and Shechem went to see Jacob, who had heard that his daughter had been rendered “impure” by Shechem. Jacob’s sons were furious about the treatment of their sister. However, they felt powerless to oppose the king (who, after all, had a walled city filled with armed men nearby). So, Jacob and his sons played for time.

Hamor asked Jacob’s permission for Shechem to marry Dinah. He further proposed that Jacob’s family become a part of the family of his city. Perhaps noticing that Jacob had eleven unwed sons, Hamor proposed that Jacob’s family could intermarry with his people. Jacob’s sons replied that it would only be possible for Dinah to marry Shechem – and it would only be possible for them to intermarry with the people of Hamor’s city – if all the men of the city agreed to be circumcised.

Hamor took this message to the people of his city. He told them about the wealth of Jacob and his sons. Why should a little foreskin stand in the way of acquiring all those flocks and cattle? The men of Hamor’s city were circumcised. Once they were incapacitated by the pain of the surgery, Simon and Levi, two of Jacob’s sons, entered the city with swords and killed every man there, including Hamor and Shechem. They took Dinah from Hamor’s palace and brought her home, while the other brothers plundered the city.

Happy ending? Not so much. Just deserts for the abduction of Dinah? It does not seem very just to us. Does the Bible condemn what Simon and Levi did? No, but it does not condone it, either. After Simon and Levi murdered the men of the city, Jacob complained that their actions would only bring trouble to him and his family.

When other cities find out what you boys have done, he said in effect, they will take revenge against us and we will be defenseless. Later, on his deathbed, Jacob told Simon and Levi that their anger was fierce and cruel. He chastised them, but his words were hardly those of a moral exemplar. He never said that their actions were evil and wrong.

In fact, Simon and Levi are the only characters in the story who offer any moral interpretation of what has happened, albeit their interpretation is a troubling one. “Should our sister be treated like a whore?” they told Jacob to justify their actions.

What are we supposed to make of Jacob’s passivity, his lack of moral outrage, and his self-centered response? What shall we say for the mute Dinah – the woman who is the center of the story’s action, whose perspective is entirely ignored? Why is this bloody, gruesome story even in the Bible? What are we supposed to learn from it?

The biblical story, I believe is primarily about Jacob and his relationship with his sons. Jacob – the third patriarch, the son of the awestruck Isaac and the grandson of the ever-faithful Abraham – is never portrayed as a man of pure ideals in Genesis. He is a person, like all of us, who is a series of compromises. He is faithful and grateful to God, but he also relies on his abilities to decide and do things for himself without outside help. He faces life’s tough challenges with thoughtfulness and intelligence, but he is also willing to use his smarts to take advantage of others. He is always “looking out for number one,” and it is sometimes hard to tell who is Jacob’s number one: God or himself.

Jacob represents a relationship with God for the real world. The story of his daughter who is abducted by a rich man’s son is just one more challenge he must face with intelligence and guile. It is a story in which he has to manage sons who are less thoughtful than he is – sons who are more captives of their anger and fear than he is.

The story of Dinah, as it is told in the Bible, is a story about making imperfect decisions in an imperfect world and dealing with people who are prone to act out of anger and hatred when caution and restraint would be better. We can all relate to that experience in some way.

But it is not enough for us. We need to be able look at this story and see more. The Bible may not care about what women think, but we sure do. We need to be able to say ‘No’ to the way that human lives are treated so cheaply in this story. We need to be able to say ‘No’ to the way that women’s lives, experiences, desires, sexuality, thoughts and feelings are ignored in this story. We need to plumb more deeply into the depths of the story and find other meanings.

That is what Anita Diamant did with her novel The Red Tent. The book, published in 1997, hit the New York Times best seller list because it gave a voice and a life to women who had previously been ignored in the Bible and in our society. The book hit a chord and sent out a message that millions of people were waiting to hear.

Anita Diamant’s Dinah is not just a victim. Diamant follows hints in the text of the biblical story to find that Dinah was not raped. She heard the sweet words that Shechem spoke to her heart. She chose to depart from the ways of her father and brothers to find love and meaning in her life in a way that suited her, not as it might suit her male relatives. After Shechem was murdered by her brothers, according to Diamant, Dinah ran away and made a life for herself as a midwife, a woman whose life was spent moving among other women, giving voice to their stories as well as her own. It is a wonderful novel and I recommend it to everyone who wants to discover that the Hebrew Bible is still speaking to us, if we are willing to listen to new interpretations and to find our own.

In Anita Diamant’s own words, the tree of Jewish tradition is made up of roots, trunk, branches and leaves. Who is to say that the deepest roots have more legitimacy than this year’s new growth? The book is a celebration that our tradition continues to grow and there are new truths and meanings yet to be discovered.

I will be watching the Lifetime Channel’s version of the story on Sunday and Monday nights. My expectations, I admit, are not very high. It is, after all, a movie made for television. But I am hopeful to see some new growth on that tree that is still growing.

Shabbat shalom.

Other Posts on This Topic:

Vayishlach: Let's Get Small

Vayishlach: The Closest We Can Get to the Face of God

RSS Feed

RSS Feed