ישימך אלהים כאפרים וכמנשה

"May God make you like Ephraim and like Manasseh."

For girls, the blessing begins:

ישמך אלהים כשרה רבקה רחל ולאה

"May God make you like Sarah, Rebecca, Rachel and Leah."

The girls' blessing makes obvious sense. It is natural that we would bless our daughters with the wish that they grow up to have the values and accomplishments of the four matriarchs. Sarah was a woman who endured anguish as a barren woman yet faithfully persevered. Rebecca was the clever "power behind the throne," who skillfully manipulated events to assure the best outcome for all. Rachel was the patient woman who stood up against her uncle Laban's deceptions and triumphed in the end. Leah was the unloved but strong-willed wife who kept true in her devotion. These women have been praised for their strength and piety since ancient times. There is even a classical midrash (Seder Eliyahu Rabbah 25) that says that God rescued Israel from Egypt only because of the merit of the matriarchs (but not the patriarchs).

In contrast to these great women role models, why do we wish our boys to be like, of all people, Ephraim and Manasseh? Who were Ephraim and Manasseh, anyway?

The answer to these questions can be found in this week's Torah portion (Vayechi). The portion at the end of the book of Genesis completes the story of Joseph, the second-to-the-youngest of Jacob's twelve sons. He was his father's favorite, but that favoritism led to tragedy. Jacob's older brothers resented and hated Joseph. They sold Joseph into slavery and deceived their father into thinking that he was dead. Nonetheless, Joseph rose up from slavery and imprisonment to become the viceroy of Egypt, Pharaoh's second-in-command. When Jacob found out that his long-lost son was still alive, he went down to Egypt to see his son again in his final days.

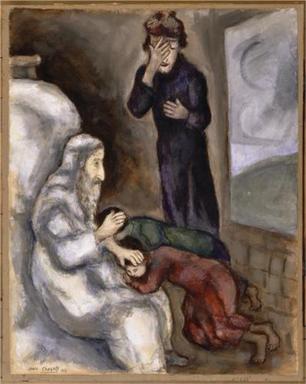

Joseph had two sons, Manasseh and Ephraim, when his father came down to Egypt. Upon seeing them, Jacob told Joseph to bring the boys to him "that I may bless them" (Genesis 48:9). Joseph carefully arranged the boys so that Manasseh, the older son, would be opposite Jacob's right hand and Ephraim, the younger, would be opposite the left. This was the proper arrangement for Jacob to give the superior blessing of the right hand to the older son.

However, Jacob had other plans. The Torah says that Jacob "stretched out his right hand and laid it on Ephraim's head, though he was the younger, and his left hand on Manasseh's head" (Genesis 48:14). In this strange posture, with his arms crossed, he blessed the two boys.

When Joseph saw what his father was doing, he tried to correct him by putting each of Jacob's hands on the head of what he considered to be the correct son. But Jacob just said, "I know, my son, I know. He (Manasseh) too shall become a people, and he too shall be great. Yet his younger brother (Ephraim) shall be greater than he, and his offspring shall be plentiful enough for nations" (Genesis 48:19).

Isn't it interesting what each of these two men – the long-separated father and son – imagined the other one was thinking? Joseph thought that his father was repeating the same mistake he made when Joseph was a child by favoring the younger son over the older. Jacob assumed that Joseph, now a powerful and privileged ruler, was trying to protect the privilege due to his older son. Jacob reassured Joseph that the older son would get his due, but that the younger would be the greater.

When we read this story, we frequently see Jacob's crossed arms as the final example in the book of Genesis of the younger son triumphing over the older. It is a theme that recurs throughout the book. It is the repetition of Abel being favored over Cain, Isaac being chosen over Ishmael, Jacob displacing Esau, and Joseph ruling over his ten older brothers. We think of Jacob's blessing as yet another case of the Genesis' favorite theme: younger brothers who take the place of older brothers.

However, a close reading shows that Jacob's switcheroo with Ephraim and Manasseh is different from the triumph of the other younger brothers in Genesis. Neither of Joseph's sons would rule over the other. (In fact, Ephraim and Manasseh would become the progenitors of the two most powerful tribes in ancient Israel, closely allied to each other, not rivals.) This is not the story of overthrow; it is a story about shared mutual success among peers. Here, at the end of the book of Genesis, we have a story that embodies the famous verse from psalms: "הנה מה טוב ומה נעים שבת אחים גם יחד," "See how good and pleasant it is when brothers dwell together" (Psalms 133:1).

This is what Jacob had in mind when he ordained that Ephraim and Manasseh would be the model for blessing Jewish children. He said of them, "By you shall Israel invoke blessings, saying, 'May God make you like Ephraim and Manasseh'" (Genesis 48:20).

The book of Genesis ends with a moment in which the persistent themes of parental favoritism, fraternal resentments, and family dysfunction are finally resolved. Parents mellow in their old age and turn their old bad habits into love. Children learn that they don't have to fear passing down the scars of their own upbringing onto the next generation. In time, we learn to correct our mistakes in life, not by rejecting our past, but by transforming it.

Just as Jacob said we would, we still bless our sons with the wish that they be "like Ephraim and Manasseh." We wish for them a life in which success is not the product of rivalry and resentment, but the outcome of peaceful and loving coexistence. Our best blessing for our children is that they enjoy each other's successes without seeing them as a threat to their own success. We wish our children the ability to get along with each other and to know that they are blessed – just as they are.

Other Posts on this Topic:

Vayechi: Repair of the Dysfunctional Family

Toledot: Letting Go of the Struggle

RSS Feed

RSS Feed