What is a leader? What qualities make a person worthy of leadership? What style of leadership, ultimately, is the most successful? In the book of Exodus, we recognize two distinct styles of leadership that could not be more different from each other.

Pharaoh seems to embody the attributes that we stereotypically associate with a strong leader. Pharaoh was decisive in confronting the threat that he saw in the growing number of Israelites in his kingdom. He was shrewd in the way that he placed taskmasters over the Israelites to force them into slavery and to build military cities for him. Pharaoh was cunning in the way that he secretly instructed the midwives to allow the Israelite’s baby boys to die in childbirth.

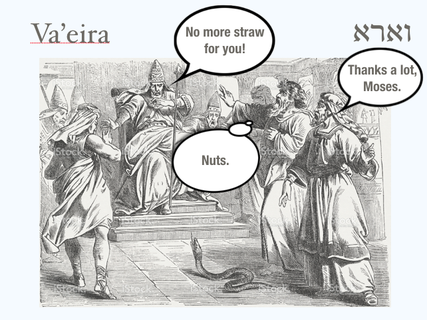

When Moses and Aaron appeared before Pharaoh and asked him to free the Israelites, Pharaoh was confident and determined. He refused to let the slaves go and he even made their servitude more harsh by denying them the straw they used to make bricks. When Pharaoh’s advisors told him that they feared the kingdom would be lost if he did not change course, he adamantly brushed them aside and kept his resolve. When the slaves did escape, Pharaoh ruthlessly employed his superior army to bring them back.

Pharaoh is everything we expect of a ruler who acts with an iron fist and a determination to work his will upon others. Yet, the book of Exodus also depicts Pharaoh as a failure and, even, as a buffoon. His plan to control and destroy the Israelites was completely thwarted. The more he oppressed them, the more they grew in numbers. The two women he enlisted to kill the innocent baby boys easily tricked him and he was utterly deceived by their simple lies. His determination to defy the demands of Moses and Aaron proved disastrous. In the end, he lost everything: his slaves, his farmlands, his cattle, his entire army, his own firstborn son, and his nation.

What went wrong for Pharaoh? Why does the book of Exodus overturn and undermine all of the images we have of powerful leadership? What is the book trying to tell us about Pharaoh’s style of rule?

The book of Exodus gives us another model of leadership – that of Moses. Wherever Pharaoh seems strong and decisive, Moses appears to be weak and vacillating. Moses did kill Pharaoh’s taskmaster who was beating an Israelite slave, but when he was discovered, Moses ran away rather than confront Pharaoh. Rather than come to terms with his past, Moses gave up the life of being a member of the royal household and became a simple shepherd. When God called to Moses and told him to return to Egypt to free the Israelites, Moses put up a pathetic refusal, saying that Pharaoh would not listen to him because he had (of all things) a speech impediment. God had to convince Moses to lead his people by saying that Aaron would speak for him and by giving him a few magic tricks to perform before Pharaoh.

Once Moses did come before Pharaoh, he produced the first two plagues that God instructed him to use: blood and frogs. After those two, Pharaoh promised to let the Israelites go if Moses would just end the plagues. Moses believed him. Once the frogs were gone, Pharaoh, predictably, returned to his stubborn ways and refused to free the slaves.

As if that was not bad enough, Moses then let Pharaoh get away with the same behavior no less than four more times. After the plague of lice was lifted, Pharaoh deceived Moses again by breaking his promise to free the slaves. He did the same thing after the plague of hail, and then after the plague of locusts, and, of course, after the death of the firstborn. Moses kept accepting Pharaoh’s word that he would free the Israelites once the plague had ended, but Pharaoh never did. The Torah does not even raise the possibility that Moses could have, you know, not ended a plague until after the Israelites were free. It never even seemed to cross Moses’ mind.

It doesn’t even end there. Once the Israelites were standing at the Red Sea with the army of Pharaoh at their backs, Moses had his greatest moment of indecision. Unable to decide what to do in a moment of crisis, Moses must have called up to heaven for an answer. God had to shout down to him, “Why do you cry out to Me? Tell the Israelites to go forward!” (Exodus 14:15).

What kind of a leader is this? Moses is nothing we expect from a leader. Rather than being bold and decisive, he dithers, he changes his mind, he allows himself to be deceived when he has no reason to believe the words of a villain. Why then does he succeed? What is the book of Exodus trying to tell us about Moses’ style of leadership and what it means to be a leader?

The Torah wants us to recognize that everything we think we know about leadership is wrong. Pharaoh is not a great leader. What seems like resolve is actually just stubbornness. His refusal to take good advice is denial of reality and delusion of grandeur.

And, of course Pharaoh has delusions of grandeur! He thinks he's a god! And he relies on people believing that he is a god. To compromise or capitulate to Moses in any way would be an admission that he is not. It would be a threat to the entire basis of his rule over Egypt.

Leaders like Pharaoh, who insist on complete domination and the subservience of all to their will, always base their authority on a lie. Such rule always is doomed to collapse — to be exposed as buffoonery. Once the lie is found out, once the truth is known, the domineering leader’s seeming resolve and strength are proven to be nothing more than false bravado and egotism. The house of cards comes crashing down. The mighty army is drowned in the sea.

And what of Moses and his style of leadership? Note that, in the story, Moses really does have great divine powers at his disposal, but he does not rely on them. In fact, he lets go of that power at the very moment when he might have used it to crush his opponent. Instead, Moses’ most powerful quality is the quality we are least likely to associate with power. It is his humility. Over and over again, Moses behaves as a man who knows that he is not God.

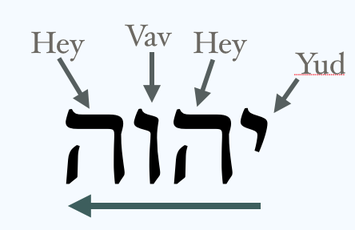

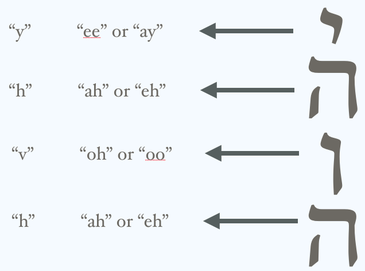

This week’s Torah portion, Va’eira, opens with God telling Moses as he is about to confront Pharaoh for the first time, “I am Adonai.” Moses hears it, and he recognizes that this is all he needs to know. God is God, and he is not.

Moses is not a powerful leader because he knows how to take decisive, bold action. Rather, he is a great leader because he knows that his fate and the fate of the world around him is not in his hands. He knows the truth that he is human and that there is something beyond him that directs his life’s journey. Despite all the power that is given to Moses by God and by the Israelites who follow him, Moses knew this truth. Knowing it, he could never be seduced into believing that he was himself a god.

That is the great lesson we learn from the confrontation between the leadership styles of Pharaoh and Moses. A true leader has no use for threats, deceit, manipulation, and abuse of power. Such traits only prove a leader to be a weakling and a failure. True leadership is knowing in all humility that redemption and victory come from knowing ourselves to be human and that we live in the light of a power beyond ourselves.

May you become the true leader of your own life, and may we all live in the light of truth.

Shabbat shalom.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed