– Exodus 12:15-16

From the Torah, it seems pretty clear how long Passover is supposed to be. The festival begins with one no-work day (a "sacred assembly") and ends on the seventh day with another no-work day. There is no mention at all of two days of observance at the beginning. There is no mention of an eighth day. Why, then, did so many of us grow up with two seders at the beginning of the holiday and a total of eight days of Passover?

The answer has to do with the Jewish calendar, the problem of communication over long distances in the ancient world, and the human habit of continuing established traditions even after times have changed.

The Torah says that the first Passover festival begins "In the first month [Nisan] from the fourteenth day of the month at evening" (Exodus 12:18). That would actually be at the very start of the 15th day of the month, just as the sun is setting. Since the months of the Hebrew calendar are determined by the phases of the moon, the first day of Passover should always begin on the 15th day of the lunar cycle – right around the time of the full moon. But you have probably already anticipated the problem: How do you know for sure which day was the first day of the lunar cycle? If people disagree about the date of the new moon, the whole calendar would be useless and people would celebrate the festival on different days.

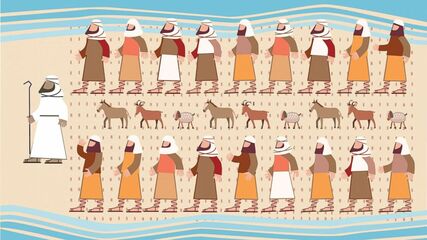

The ancient Israelites solved this problem by setting up a tribunal in Jerusalem to determine the beginning of the new moon. Witnesses reported the sighting of the moon to judges and they determined the day of the new moon based on testimony. The ruling of the judges was final, and everyone agreed to abide by it.

That system worked great for a few hundred years, until Jews started spreading out over a large geographic area. When the Jewish community in Babylon (modern Iraq) wanted to know which day to start celebrating Passover, they had to hope that they would get word from Jerusalem within two weeks about which day was the first day of Nisan. It did not always work out that way. Four weeks was enough time to get the news, but two weeks was cutting it close in a world without cell phones, or even a pony express. They could not know with certainty which day the festival started. Fortunately, there were only two possible choices.

The phases of the moon last an average of 29.53 days. (Because the earth's orbit around the sun and the moon's orbit around the earth are elliptical, there are variations in the length of a lunar month.) That means that the length of each lunar month must be either 29 or 30 days. Ancient Jews in Babylonian didn't know what day would be the date of the first day of Passover, but they did know it had to be either the fifteenth day after the 29th day of the previous month, or the fifteenth day after the 30th day of the previous month.

Their solution was simple. They celebrated the festival on both dates. They would have two days of sacred assembly at the beginning of the festival and two days at the end. To do that, they had to add an eighth day. (Which was really the seventh day following the second possible first day. Have I confused you enough already?)

Of course, this system of adding days to the holiday was unnecessary if you lived close enough to Jerusalem to get the news about the judges' decision within two weeks. That is why they did not change the holiday within the Land of Israel. To this day, all Jews celebrate only one seder and only seven days of Passover in Israel.

In late antiquity, Jews stopped using direct observation of the moon to determine the calendar. They decided to switch to the more reliable system of mathematical models that predict the appearance of the moon. That is why we can say with certainty today which day Passover will begin next year, the following year, and a hundred years from now. Just do the math.

However, even with the innovation of a fixed, mathematical calendar, Jews outside of the Land of Israel continued to celebrate the extra day. They repeated all the customs of the first day on the second day, including the seder, and all the customs of the seventh day on the eighth day. By that time, it had become an ingrained observance that Jews were unwilling to change. Passover, at least outside of the Land of Israel, had been transformed into an eight-day holiday.

That is, until the beginning of the Reform Movement in the 19th century. The early Reformers said, "This nonsense has been going on for too long already! The Torah says that Passover is seven days. We're not going to celebrate it a day longer!" (or, words to that effect). This is why Reform Judaism celebrates only one seder and only seven days of the festival, both inside and outside of Israel.

There is an added complication to this system in a year like this year when Passover begins on Shabbat. To those who observe Passover for eight days, there are two Shabbats that fall during Passover this year. For those who observe seven days, there can only be one Shabbat in any Passover. On April 27, 2019, many Jews will be celebrating the eighth day of Passover and reading the Torah portion assigned to that day of the festival. However, at the congregation I serve (and many other Reform congregations), we will be resuming the regular cycle of weekly Shabbat Torah portions.

That would create a situation where Reform Jews were out of sync with orthodox and Conservative Jews outside of Israel on the weekly Torah portion. Indeed, all Jews in Israel and many Reform Jews worldwide will be out of sync with the rest of the Torah-reading world after this coming Shabbat until early August.

I don't like that. I think it is important for Reform congregations to read the same Torah portion each week that is read in nearby Conservative and orthodox congregations. So, instead of going out of sync, the congregation I serve will split next week's Torah portion (Acharei Mot) in two – reading the first half this week and the second half the following week. That choice will keep us in sync after only one week.

You can call that decision Solomon-like. (He also liked cutting things in half). Or, you can just say that we are keeping up with the times.

Other Posts on This Topic:

Soul Searching

One Seder or Two?

RSS Feed

RSS Feed