I have to admit that there is one common question that people use to start a conversation that always troubles me. It’s a simple question that most people seem to answer with ease, but it has always been difficult for me.

"Where are you from?"

Where am I from? Well, I was born in Norfolk, Virginia, while my father was serving in the U.S. Navy and was stationed there. I could say that I’m from Virginia, but I actually only lived there for a few months while I was an infant. I have no memory of living in Virginia during that first year of my life. I’m not really from Virginia.

I spent the next part of my life living on the East Side of Manhattan. Those were some very important years for me and I have many memories of growing up in New York City, traveling uptown and downtown on city busses, visiting my grandparents' apartment south of Central Park, going to museums and doing the things that city kids do. However, I left Manhattan when I was ten years old, so I didn’t go to high school there. I didn’t learn to drive there. I didn’t make many lifelong friends there. I did not do a lot of things that people associate with “the place where I grew up.” I’m not really from Manhattan.

Most of those teenage, identity-building experiences for me were in the suburbs. My family moved to Westchester County when I was ten and I eventually graduated from Scarsdale High School. It never really felt like home to me, though. The culture of the suburbs turned me off when I was a kid. I didn’t like the cliques and the country clubs. I was turned off by the 1970s version of preppy materialism. Even though most of my oldest friends are people I met and went to school with in the suburbs, I never really felt like I was from there.

So, where do I really feel like I am from? For most of my adult life, I have felt comfortable answering that question by saying: Here. I’m from where I am right now. I moved to Boston a year after I graduated from college and I felt right at home there in a way that I never felt about New York City. After rabbinic school, I lived for a decade in Western Massachusetts and I took to it very quickly. The town where I lived seemed like my hometown in no time.

I’ve only been in Rhode Island for just over a year now, and it, too, seems to fit me like a glove. When people ask me where I’m from, I say with hardly any hesitation, “I’m from Rhode Island.”

That’s nice. I think it is a good and comfortable thing to feel at home in the place where you live. My wife and I often say to each other, “You are my home,” and that is our deep, truest truth. "Home," as they say, "is where the heart is." That saying, to me, does not mean that you can only find your heart by going home. To me, it means that when you find your heart, you find your home.

I think it is better to be at home where you are than to always be thinking about some other place as being your "real" home, as if we always carry the shadow of our former homes around with us and long to return to them. I’ve never felt that way in life and I’m glad for it.

However, that does not eliminate the discomfort that comes when someone pushes me on the question of my place of origin and says, “No. Where are your really from? Where do you come from?”

I don’t really have a place on a map that is an answer to that question. It is not Virginia. It is not New York City. It is not Scarsdale. It certainly is not Florida, the place that I left to come to Rhode Island. (Actually, it can be hard to find anyone who is really from Florida, even in Florida.) The only answer that really makes sense inside my own head to the question, “Where are you really from?” is right here – with my family, the people I love, and the things that I care about. That is my home.

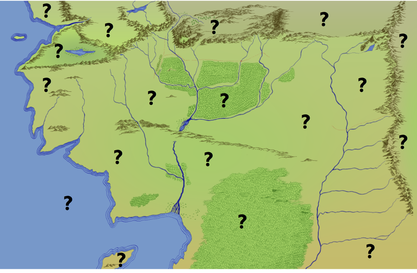

So, it is odd when I consider that this befuddlement with the question, “Where are you from?” is also a befuddlement that has followed the Jewish people from our very beginning. In this week’s Torah portion, God tells Abram (who will later be renamed “Abraham”) to leave his land, to leave his birthplace, to leave the house of his fathers and to find a new home in “a land that I will show you.”

Abram is told that the physical location from which he comes does not define him and will not define his future. He will, for the rest of his life, have to find an answer to the question, “Where are you from?” with a different place and with a different kind of answer. It is almost as if God is telling Abram, “From now on, your home is with Me. It is wherever you and I are together.” That is, in a way, a lovely way to think about home and a lovely way to think about God. But it can be a bit uncomfortable. It's a bit like not really having a place from which to be from.

This, indeed, was the predicament of the Jewish people for most of our history. We began to grow used to the idea of not having a home when we were exiles in Babylon during the 6th century B.C.E. The ancient Israelites returned to their land after the Babylonians were defeated by the Persians, but the memory of being homeless stuck with us for a long time.

After the fall of Jerusalem in the year 70 C.E., some six hundred years later, we were exiles again. The memory of the first exile helped us make sense of our landless existence for the next two millennia. For the many centuries in which the vast majority of the Jewish people lived outside of the land of Israel, we got used to thinking of our homeland as a faraway memory – more of a idealistic dream than a real place. We grew inured to the idea that we were a homeless people and that our homeland was something that existed in our sacred books more than it existed in on the earth.

That, of course, changed in the nineteenth century with the birth of the modern Zionist movement. Jews had always had some presence in the land of Israel, but starting in the 1880s and 1890s, large numbers of Jews started moving to Eretz Yisrael, the Land of Israel, and making it their home. They tilled the soil, drained the swamps and discovered a depth of dirt-under-the-fingernails connection with the land unknown since ancient times. Theodor Herzl, the founder of Modern Zionism, taught us that our dreams of a homeland did not have to reside only in books. “If you will it into reality,” he said, “it need not be just a dream.”

So, here we are now, sixty-seven years after the founding of the State of Israel. We can longer say, as a people, that we do not have a national hometown. Israel is that hometown, even for those of us who have never been there. When the nations of the world say to us now, “Where are you from?” the Jewish people answer proudly, we are from the land of our ancestors, the land of Israel. It is our home. It is where we are from.

But that answer sounds and feels differently coming from Jews than it would sound or feel from just about any other people. There isn't the same catch in the throat from a Frenchman who says, “I am from France,” and there is no moment of hesitation from a Bolivian who says, “I am from Bolivia.” For Jews, it is different. There is so much history, so many tears, and so many intervening centuries of separation that make us shiver a bit – even for the nativeborn Sabra – when we say, “I am from Israel.” It means something more complex and bittersweet for us, I think, than for most people.

Over the last few weeks, we have seen some desperate challenges to our claim to our own homeland. A United Nations cultural agency took up a resolution this week that claimed, essentially, that the Jewish people have no historical claim to the land of Judea ("Jew-dea"!), the land that bears our name. In the streets of Jerusalem and throughout Israel, a small number of Palestinian Arabs have picked up knives and swung them in our faces to declare that we are not really from the land that they claim. Some have killed and some of us have been killed for the audacity of living in our own home. It has been a painful few weeks to be a Jew and to affirm our home in the land of Israel – even more so than usual.

But it has never really been easy for us. Abram had to learn to be not from the place where his mother give birth to him and the place where his father taught him to shepherd sheep. It became his place because it was the place where he fell in love with God and the place where he made and loved his family with God.

We, too, diasporan Jews, have had to deal with the strange notion that our home – our real home – is someplace else. The place where our heart knows its deepest truth and where we are really from, is the land that we built, the land that we are still building, and the land that we will forever build in the land of Israel.

Shabbat shalom.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed